11 Sept 2013

CITY AT THE END OF TIME

In the Corridors of the KGB

From the sunlit square in the center of Vilnius, it looks like any of the other massive, ornate facades that dot the city as government buildings. Lithuania may be newly independent, but there are still plenty of reminders of its medieval glory days as one of the largest countries in Europe. There is nothing glorious, however, about this building. For fifty years it was the headquarters of the KGB and the even more dreaded Stalinist NKVD.

The enormous Lenin statue has been toppled and removed from the plinth outside. Now on the sidewalk stand a pile of heaped stones, littered with tiny crosses, amulets, bits of paper and once-lit candles. A memorial to those who had been taken inside the building . . . and never brought out.

The flowers will linger, but not nearly as long as the memories. Every Lithuanian family lost a member to the hidden torture chambers under this square.

My sons and I go past the memorial, down through a tree-lined courtyard, and around to a side entrance. The sign reads (in Lithuanian) “The Museum of the Genocide of the Lithuanian People.” I had thought it would be an instructive moment for the boys; a chance to see first hand the heavy clamp of secret police on an oppressed populace. They hope for displays on the workings of the KGB: miniature hidden cameras, details of past escapades, clever killing devices.

Inside the building a hallway leads us through photographs of labor camps in Siberia and of stiff, unsmiling families gathered somewhere in the woods. A silent man sells us tickets and points us down a set of stairs. . . .

At first I’m disappointed. We’ve come out in a shabby, ill-lit hallway with a series of iron green doors propped open and two shuffling old men poking in and out. Where is the drama, I wonder? The boys edge doubtfully forward, seeking evidence of James Bond-ian villains and looking past the drabness.

We start at a tiny holding cell with a pinhole for guard viewing. Alex, the older boy, locks young Evan inside—just for a moment; to feel the darkness and the confinement—and when he comes back out I read the sign to them. This had been a prisoner’s first stop, and often took up to twelve hours. We move on past guard rooms, a shower and toilet area with buckets in the corners, cells built for two—which had housed as many as twenty— and on into the gloom.

The two old men ahead of us are mumbling to each other in monosyllables and I wonder how intimately they are acquainted with this place. It is said that every family in Lithuania lost somebody to this corridor, though for many it was only a first stop before other destinations.

Here is a room piled with burlap sacks stuffed with paper. At the end, when the Soviet Union collapsed with surprising quickness, KGB officials were found filling the bags with documents in a vain attempt to spirit them out of the country. Now they stand in the comer, still unread, but mute witness nonetheless.

Now we are deep into the hallway. On our left is a room with only a cement floor and a tiny pedestal the size of a dinner plate that projects upwards a couple of feet above the floor. The water torture room. Here the prisoner stood naked on the plate, or sat in the water (bone chilling cold in the winter) and attempted to avoid falling asleep. Nobody hauled you out when you fell. Three or four days was the longest anybody lasted. Beyond this is a tiny room with dirty grey padding on the walls and against the far wall a black cloth spread out like a misshapen spider trying to climb to freedom. This is a straightjacket, unfurled before binding and, despite my best attempts, my imagination puts me in it. Just for a moment; then we move on.

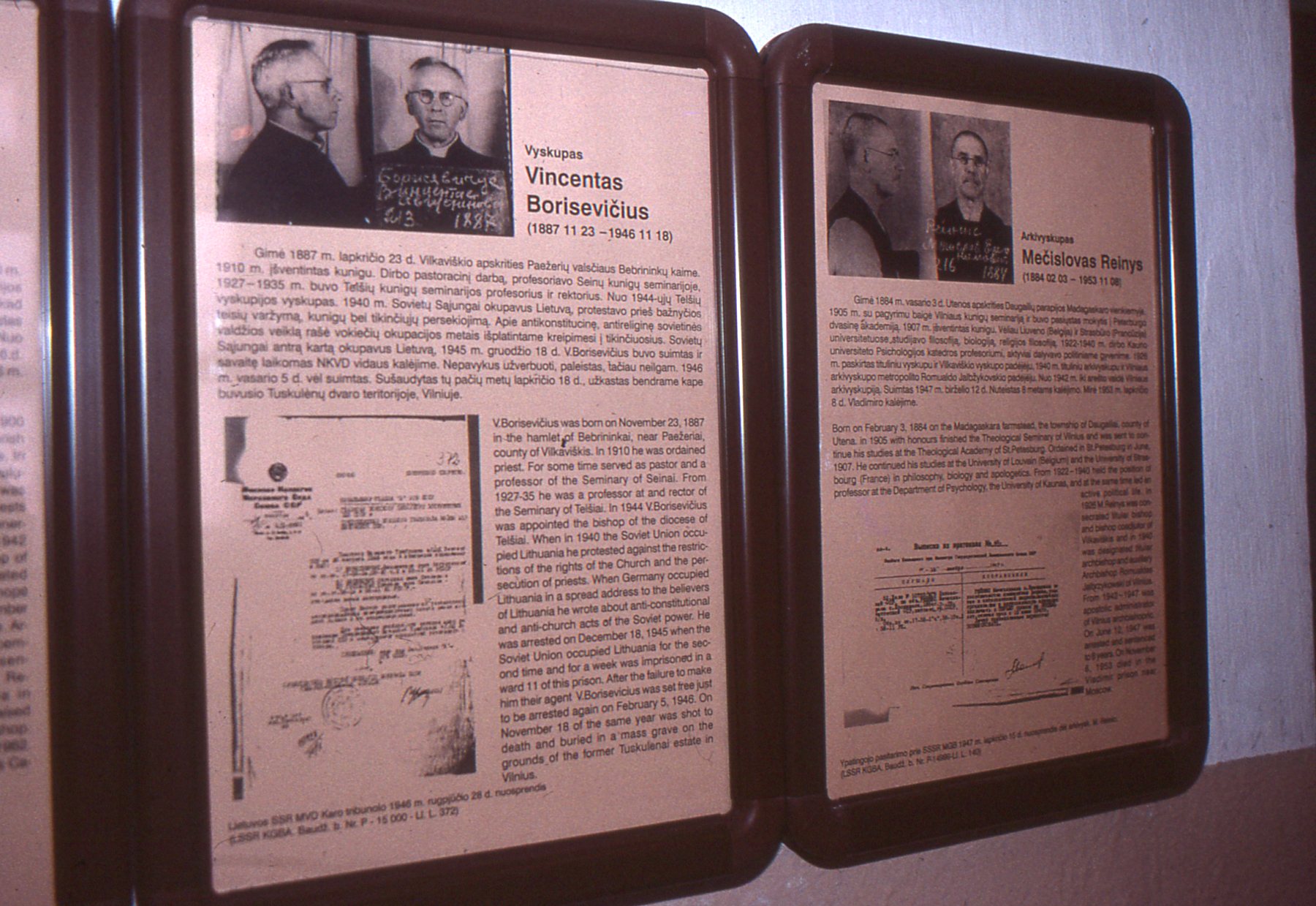

Even archbishops weren’t safe from the KGB. In an intensely Catholic country like Lithuania, this was sacrilege.

More cells, mug shots of captured archbishops, another guard room. The boys have gone quiet and no longer peer quickly into whatever comes next.

“I think we should go,” says Evan. “I don’t think we should be here.”

“In a minute,” I say. “Here’s a place to step outside.”

Into a courtyard littered with broken glass, with a rusted wire fence and high walls surrounding it. A flight of rickety steps takes us up to a narrow walkway and a tiny hut. Here the guard sat, with wire mesh on either side of the walkway, and peered down at the captives taking their ten minutes daily “exercise” on the cement. Were these the moments of hope? Or confirmation of despair—that even outside there was only the grim, grey hand of the state police?

We go back inside.

“Maybe we should go.” Alex this time.

“Let’s just finish the hallway. There’s some photos down here.”

My mistake. Photos there are, of the fallen Lithuanian “forest fighters” who waged a nine year guerrilla war against Stalinist Russia. I had never heard of this war, or indeed of the forest fighters. (Does history’s ignorance make their cause even more tragic or pointless beyond belief?) But I’ll never forget them now. The photo montage is of death masks, fallen comrades in the woods, eyes eaten out by flies, bullet holes in foreheads, shabbily dressed young men and women clutching awkward rifles and the real objects of these photographs never even seen—the power of the state . . . the camera holders beyond the frame . . . shapers of the images of history . . . but never, the Lithuanians would say, of the hearts and minds of the people.

Originally published in Imago (Australia), Vol. 13, No. 3, 2001