19 October 2020

Innocence is a fragile thing. We all know that. Where we get confused is in our notion that innocence is inevitably ‘lost.’ It isn’t lost so much as it is eroded—gradually, in a series of cumulative slides downward from a childish mountain of belief.

I admit, occasionally that mountain is shaken so hard that even some of the bedrock comes crashing down from the heights. After it’s all over we pick ourselves back up and go on living. Only this time we’re standing on some of that bedrock—and we’re a little bit closer to the top.

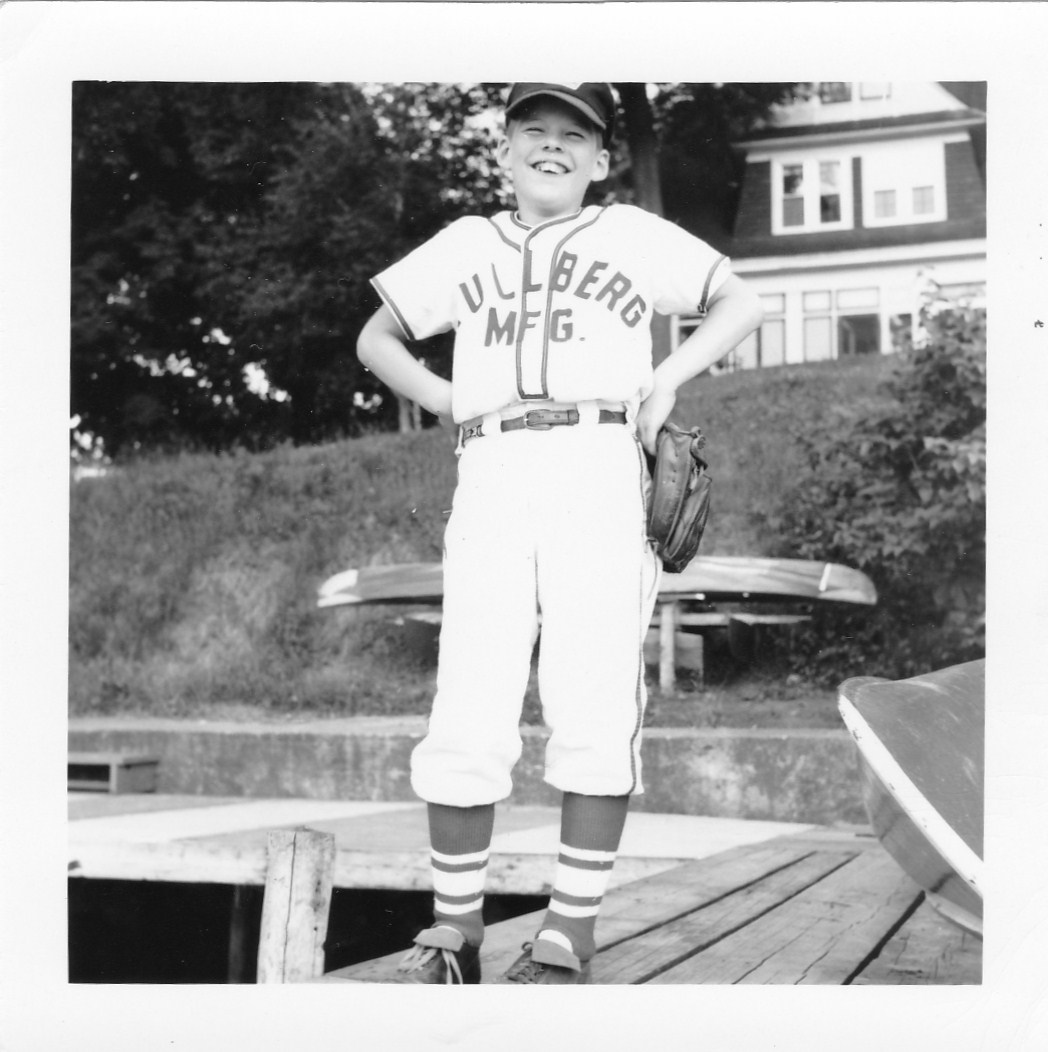

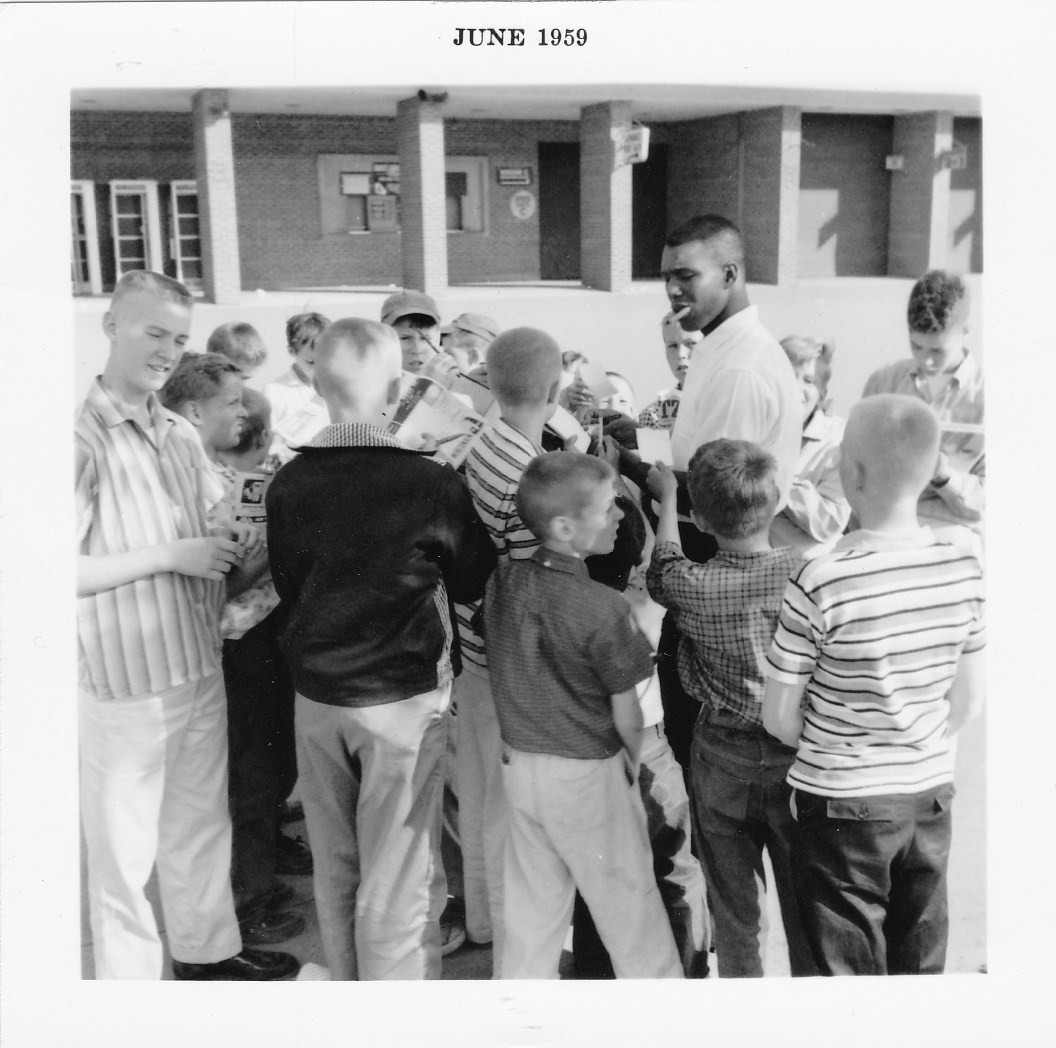

One of the first serious earth tremors of my childhood took place on October 13, 1960. It was the 7th game of the World Series—Yankees vs. Pirates. I was ten years old. To describe me as a Yankee ‘fan’ was accurate only insofar as that word is short for fanatic. They were my Team—win, lose, or winter—and had been since one night at the age of seven when I’d picked up a newspaper and seen a picture of Mickey Mantle staring me in the face.

I suppose it was a conversion experience. Overnight, the Yankees became my cause. I memorized statistics and pasted up pictures on my bedroom wall. I produced scale drawings of Yankee Stadium and painfully typed booklets of career batting records for the entire Yankee lineup. At night I tuned my transistor under the covers to fading signals from Chicago, Detroit and Cleveland. With the fervor of youth I believed in the rightness of the yearly march to the pennant—and the October battles with the infidels from the other league. I was a true believer.

I did not go un-persecuted, however. I lived in Wisconsin, where every kid worth his weight in baseball cards was a Braves fan. The ’57 and ’58 Series (which the Braves had split with the Yanks) had been particularly vicious. Twice I had been goaded into fights with the class behemoth, Butchie Barber. The bloody noses I brought home did nothing to dampen my ardor, but they were a measure of local sentiment.

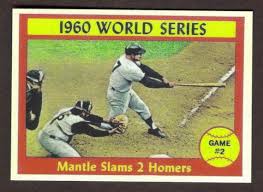

Revenge would be mine. Of this I was sure. Baseball had seen nothing like the Yankees’ M&M boys (Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris, who had finished 1-2 in the MVP balloting and were a year away from smashing a record 115 home runs between them) since . . . well, since Ruth and Gehrig. On paper, their Pirate opponents were clearly outclassed. If there was an irony in me, the schoolyard underdog, rooting against my major league equivalent, it escaped my notice. Might, I was certain, would prove right.

Through the first six games the Yankees had pounded the Pirate pitchers, winning by scores of 10-0, 12-0, and 16-3. By rights, this Series should have long since ended, but somehow the Pirates had scraped out three wins of their own, and now the whole show was riding on one final game.

1960 was the only time a World Series MVP was chosen from the losing team—Bobby Richardson drove in a Series-record 12 runs, and more amazingly, came to our church in Minnesota the very next year. Richardson played 2B, and ever after this day, so did my brother Roger.

During the Series, our teacher Mrs. O’Reilly made allowance for the fact that our attention was elsewhere, by permitting us to bring transistor radios to class so we could listen ‘quietly’ at our desks when our work was finished.

Alone, I carried my little radio back and forth each day, my NY cap pulled grimly down over my forehead, reciting to myself the years of previous pennants to avoid hearing the taunts of Butchie and his buddies who covered their frustration at the Braves’ failure to win by becoming instant Pirate fans. Once at school, I raced through my assignments and spent the afternoons with one ear glued to the tinny speaker.

Arrangements for the 7th game would be different, we were told. Interest ran so high throughout the school that the principal announced the final game would be broadcast over the school PA system. Excitement spread quickly through the class, with rude remarks whispered up the aisle in my direction.

Only one other person in the class professed loyalty to the Yankee cause. This was Leonard Millington, a rather slow boy from a farm outside of town, who seemed not quite clear as to who exactly played on the Yankees. Since he had expressed no interest in the team all season, I attributed his support at this time to be merely a passing affectation, prompted perhaps by a desire for attention, be it good or ill. I saw no hope of a true alliance (especially as he sat on the far side of the room) and turned my attention to fine tuning my transistor. I intended to have it on hand just in case problems should arise, such as difficulties with the school PA, or the principal having a change of heart.

We stumbled absently through the arithmetic lesson until Mrs. O’Reilly finally sighed and told us to put our books away. Under cover of the clattering desk tops, several bits of wadded paper hit me in the back of the head. When I turned, six boys in the back rows thumbed their noses joyfully at me and Butchie Barber shredded a Mickey Mantle baseball card into little bits.

Ah, desecration, blasphemy! I turned the other way, seething with a righteous rage. Then the PA clicked into action. It was game time.

Looking back now, I can see the game for what it really was—one of the most bizarre and exciting in baseball history. As a 5th grader, it was something more. It was a clash of titans; there was significance, anguish, and an inescapable sense that the world hung in the balance.

Things started badly. The Pirates scored two in the first and two more in the second. I took some small consolation in the fact that adversity is to be expected—the champion overcomes.

When ace fireman Elroy Face came in to relieve in the 6th there were muted jeers from the back row. He’d already stopped the Yankees three times. But things began to heat up: Yogi Berra hit a three-run homer, the Yanks added another run, and suddenly they were up 5-4. The jeering stopped.

When the 8th inning rolled around I could bear the public tension of listening to the PA no longer. I flipped on my own radio and crouched over it at my desk.

Anybody who followed the course of those last two innings will remember the tightening screws of pressure that each putout brought. The pace, the flip-flop of momentum, the chance tricks of fate all combined to provide a drama rarely surpassed in Series competition.

The Yankees scored twice in their half of the 8th and led 7-4. Things looked very good. My classmates glowered collectively over the state of events, but I beamed. I even waved jovially across the room to Leonard Millington, more than willing to share the glory. I switched off my radio and sat up to enjoy the play-by-play from the PA. Only an inning and a half . . .

Fifteen minutes later my nerves were shattered. A sure fire double-play ball (the infamous bad hop off Tony Kubek’s adam’s apple) and a squibbler to the pitcher had turned into two runs—and the lead run still on base. My stomach churned.

It nearly erupted when Hal Smith popped a 400 foot shot over the left field wall. The classroom (and Forbes Field) did erupt. The Pirates had suddenly scored five (could it really be five?) runs and led 9-7. My face was drained of blood. I felt weak. I put my head down on my desk, facing away from the other kids, and switched back on my transistor.

It couldn’t end in defeat. It just couldn’t . . .

Top of the 9th, Richardson, Long and Mantle singled—one run in, one run down. My teeth bit at my lower lip. Berra shot a ground-gripper to first that almost ended the game then and there. A burst of static, confused yells, and a long hoarse-voiced commentary from the announcer were needed to explain the maneuvers of Messrs. Berra, Mantle and Nelson (the Pirate first baseman).

When the shouting stopped and the inning ended, the Yankees had tied the game. I wiped my sleeve across my face and stole a glance at the rear of the room. Butchie Barber sat hunched darkly over a piece of rope dangling from his chair. I looked quickly away.

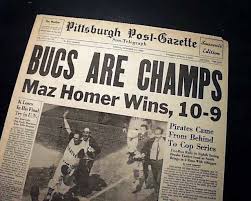

That was the end really. Mazerowski got the high fastball and the rest, as they say so often, was history. For me it was numbness. And disbelief.

I kept my head down on my desk, facing the wall. My transistor crackled with the crowd’s enthusiasm. Butchie was jumping on his desk and shouting “Yankees dive! Yankees dive!” Great cheers came echoing down the hallway from the other classrooms, but the noise seemed far away.

I kept my head down on my desk, facing the wall. I shut off my transistor.

Originally published in the Minneapolis Review of Baseball, Fall, 1982.