9 January 2017

1492 was more than just the year Columbus sailed the ocean blue. On the Iberian Peninsula in southwestern Europe, it meant the beginning of the end of the centuries’ old life of the local Sephardic Jews. The same Spanish royal duo of Ferdinand and Isabella who bankrolled Columbus also used anno 1492 to declare that Jews within their kingdom must convert to Christianity, or depart the country.

Some 150,000 chose to flee over the border into Portugal, with most settling in the mountainous regions near Spain. Jews had already been living in Portugal for at least a thousand years, contributing in many significant ways to national life. They were diplomats, cartographers, and merchants—even the previous king’s treasurer had been Jewish. But no sooner had the new arrivals begun to build fresh lives than in 1497 King Manuel I issued the same xenophobic decree to all members of the Jewish community, regardless of how long they’d been present in Portugal: convert, leave, or die.

The old Jewish quarter in Castelo de Vide looks idyllic today, but imagine the panic after the 1497 decree.

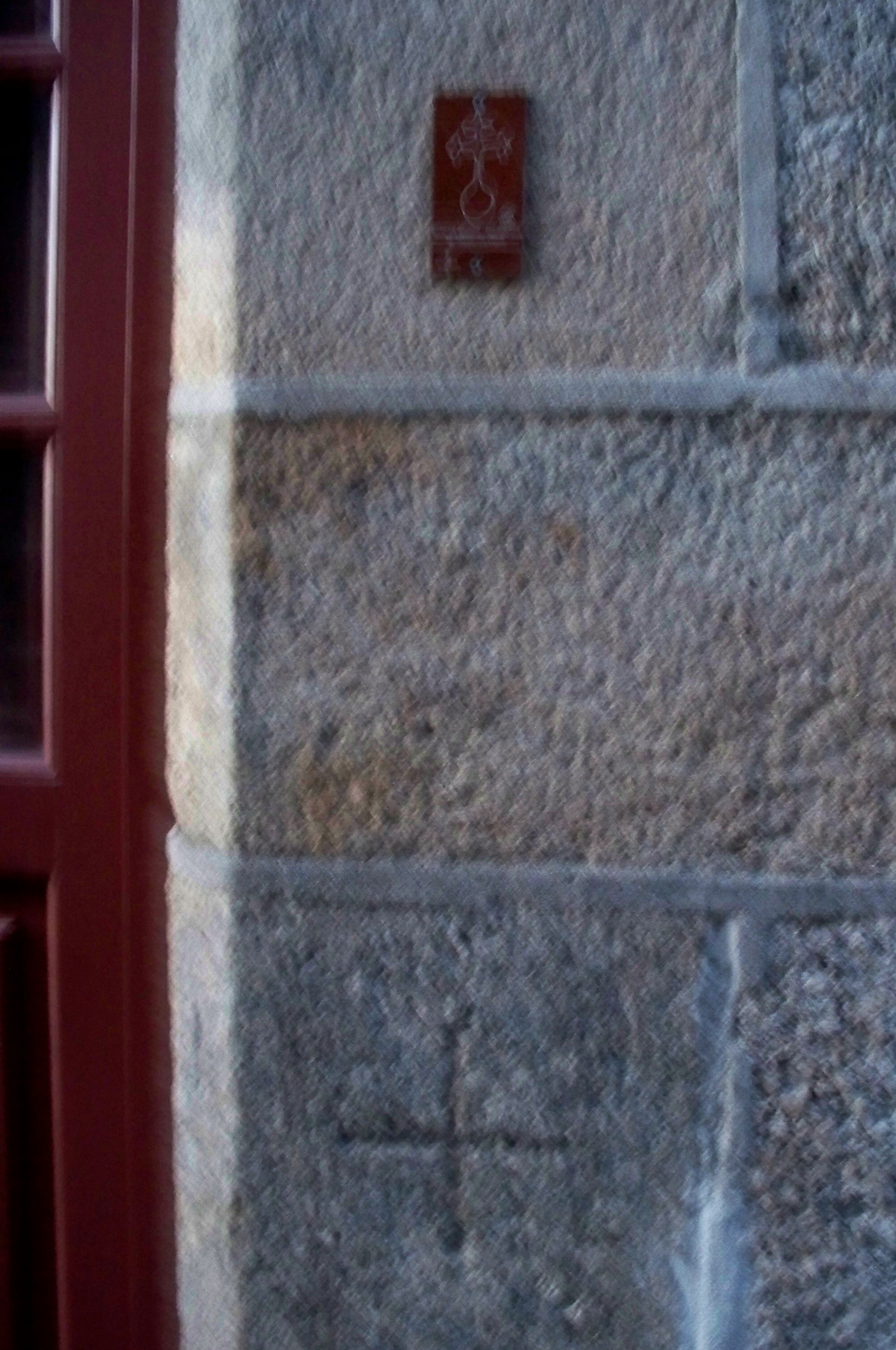

There were definitely consequences. In 1506, thousands of Jews were killed by raging mobs, and in 1536 a two-century Inquisition was begun, leading to imprisonment, torture and death for virtually everybody accused. Many fled, once again. Of those who chose to stay, most became Marranos, new converts to Christianity, whose doorposts were often marked with a cross to symbolize their status. But Marranos were not trusted, and careful attention was paid to make sure the conversion was real.

In Guarda’s Judiaria, several houses still bear the stone-etched cross that signified a conversion to Christianity had taken place.

That appeared to be the final page of yet another shameful chapter of anti-Semitism in Europe. However . . . in the early decades of the 20th century, a man named Schwarz discovered that there were actually hidden communities of Jews still active in the country, mostly in the regions of Tras-os Montes and the Beiras. This led Captain Barros Basto, a symphathizer, to conduct the “Obra do Resgate,” which was aimed to help the remaining Marranos practice their Jewish traditions openly.

Eventually, some two dozen communities of crypto-Jews (in various stages of survival) were discovered. The last to be revealed, in Belmonte, didn’t emerge until the 1980s! (Belmonte’s synagogue, built in 1297, was the oldest in Portugal.) In this community, all the Jewish traditions and secrets were handed down through the female line, unlike in orthodox Jewish practice. This gender inversion may well have been used as another layer of security from prying eyes. In any case, the Belmonte community (currently about 200 strong) is still extremely secretive about exactly which practices were maintained, and how. Marriage arrangements had been particularly difficult to sustain, and the level of inbreeding required means that many community members today suffer from hereditary diseases.

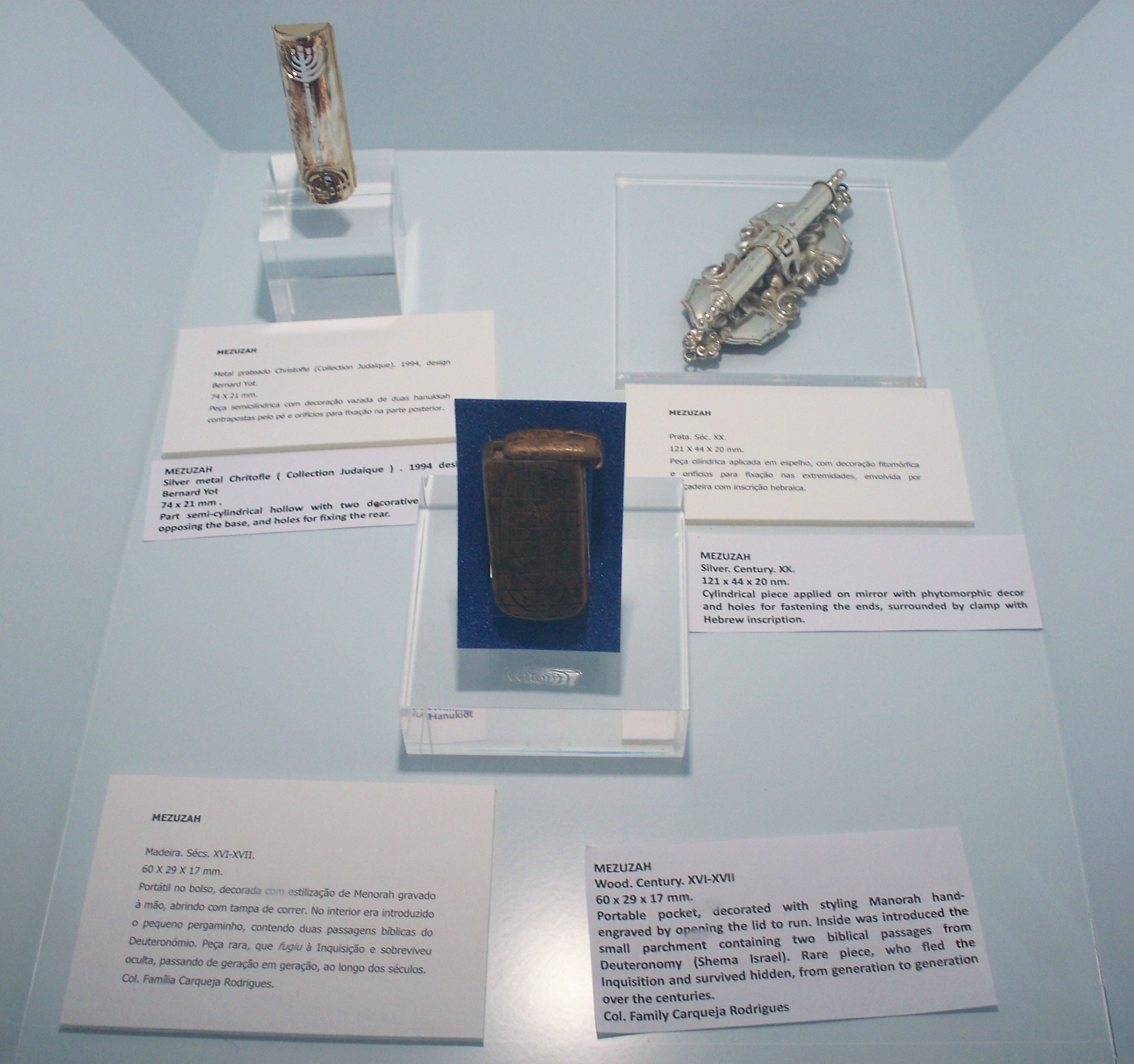

Nowadays, towns such as Castelo de Vide and Guarda post signs outlining their old Judiarias, or Jewish quarters, and small museums can be found in both Belmonte and Castelo de Vide. The contents of these museums depict those few, fragile items that were saved down through the centuries: Shabbat lights, mezuzahs, a copy of Flavius Josephus’ history of the Jews, a tiny precious Torah . . . Remnants only, to be sure, but it is that faithful remnant that carries the witness forward.