12 February 2019

As a child, I was a voracious reader. It took me years to stop reading every single billboard, every single street sign, every scrap of printed paper I came across. I burned through my school library, my town library, and the handful of Chip Hilton and Hardy Boys books stocked by our local five-and-dime and liberated by me without need for any pesky cash register transactions.

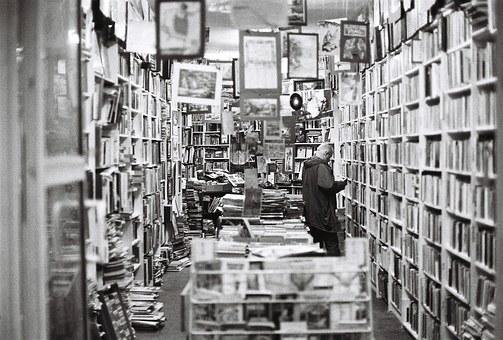

Given the parlous state of our family finances, this might well have been the limit of my acquisitions. But there was one further source of literary access: the used bookstore run by the Salvation Army down on Skid Row, which was confined (unsuccessfully) to the middle of the Mississippi River, on Nicollet Island in Minneapolis. All the stores on the Row featured used goods, except for the bars, and even there one could hardly be certain of the provenance of any given tipple.

The Salvation Army bookstore was a musty, dark place, with never-dusted shelves and a cantankerous proprietor who dozed behind a small desk. From time to time he would blink awake with a snort, glare around him as if to blame whomever else might be in the shop, and then resettle himself back in his dreaming-chair, until such time as the making of change might be required.

There were rarely other patrons in the store, but when there were they tended to be freight riders or bindle stiffs who had wandered in out of the weather, looking for a place to sleep, or piss. Sometimes both objects were achieved along the darker back aisles. Once my search for oversized picture books about knights and castles drew me along the far shelves near the cloth-hung doorway that led to the back storeroom, where my wanderings ended abruptly when I came upon a grizzled figure in a torn army greatcoat who had managed to fall asleep upright, propped on an overflow shelf of paperback romances. From the smells coming off him I could deduce that he had both imbibed a large quantity of liquor and successfully relieved himself in his pants.

I never revisited that particular back aisle—but then I never told anybody about the incident either. I knew it was all too likely that our bookstore expeditions would end, and that would be a catastrophe I could never endorse.

The first few times we went there—a gaggle of mop-haired word-hungry siblings ranging from babes in arms to my eleven years—we were escorted by Grandmom, a former school teacher from the West Virginia hills who took back talk from nobody. Ever since Granddad had retired, he and Grandmom spent half the year traveling North America in their pop-up van, Itchyfoot. (This was in the early sixties, well before a younger generation began filling the roads with live-in vans.) Each summer they’d pull into our driveway and I’d dash out to inspect the latest additions to their rolling home. We always got two shopping trips out of their visits. One was to buy shoes for each of us five children. The other was a journey to that fabled Sally Army store, where we were each allowed to select as many books as we could carry. (Since they cost 5¢ apiece, Grandmom knew we couldn’t empty her purse.)

In those early days, my attention was on completing my collection of Hardy Boys and John R. Tunis adventures, along with the occasional book on pirates, or baseball, or whatnot. I began to learn about first editions, and failed continuity across a series, and the collector’s struggle to find that last final rarity that so often is a justifiably-forgotten side remnant of some author’s oeuvre.

As I grew into my teens, I began making my way to the Salvation Army store on my own, without waiting for Grandmom’s annual visit. Now I was free to look for any old thing I pleased, with no concerns that my stack of books would be studied for “appropriateness” by any of the significant adults in my life. If I wanted to peruse The Last Days of Al Capone, or “The Bikini and Who Can Wear It,” such was my choice. One day I found The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Another time it was a slim Ace Books volume called simply Junkie, by some guy named William Burroughs. I couldn’t believe that anybody would willingly display their addiction in such a manner—or that a book company would print it.

By the time I was deep into high school, I was an expert at mining the shelves for hidden gems. This is where I first encountered James T. Farrell, via The Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan. Soon I was back for the other volumes in the Studs Lonigan trilogy. I concocted a high school research paper on the dissonance of modern youth as evidenced in the rise of motorcycle gangs thanks to stumbling on a paperback named Hell’s Angels, by one Hunter S. Thompson. On an unpainted green wooden shelf labeled “Music/Art/Movies” one day I picked up a book by an author completely unknown to me—Mezz Mezzrow—simply because of the title: Really the Blues. I was deep into discovering the blues, and bought it at once, though Mezz’s book was all about jazz, and reefer (“the mighty mezz”) and a million nights on the bandstands and stage doors of the American night.

In time, the city condemned Skid Row and both sides of the street were leveled to make way for the brand new Hennepin Avenue bridge. Life on Nicollet Island continues—there’s a small neighborhood of converted boardinghouses, a classic old inn, and the imposing brickwork of DeLaSalle High School. But the island’s real treasures—those innumerable 5¢ books with their hinted promise of bold, nefarious deeds—are lost to the winds of time. Except for the rescued ones that still populate my shelves at home, reminders of younger days.

Originally published in Tampa Review, Issue 55/56, 2018