7 April 2019

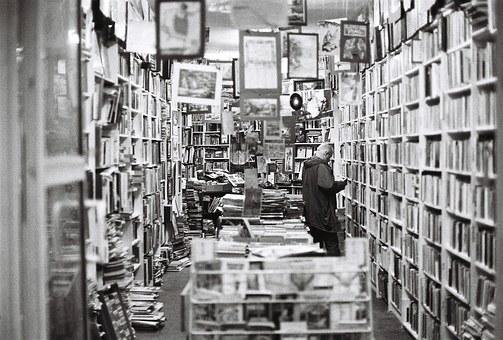

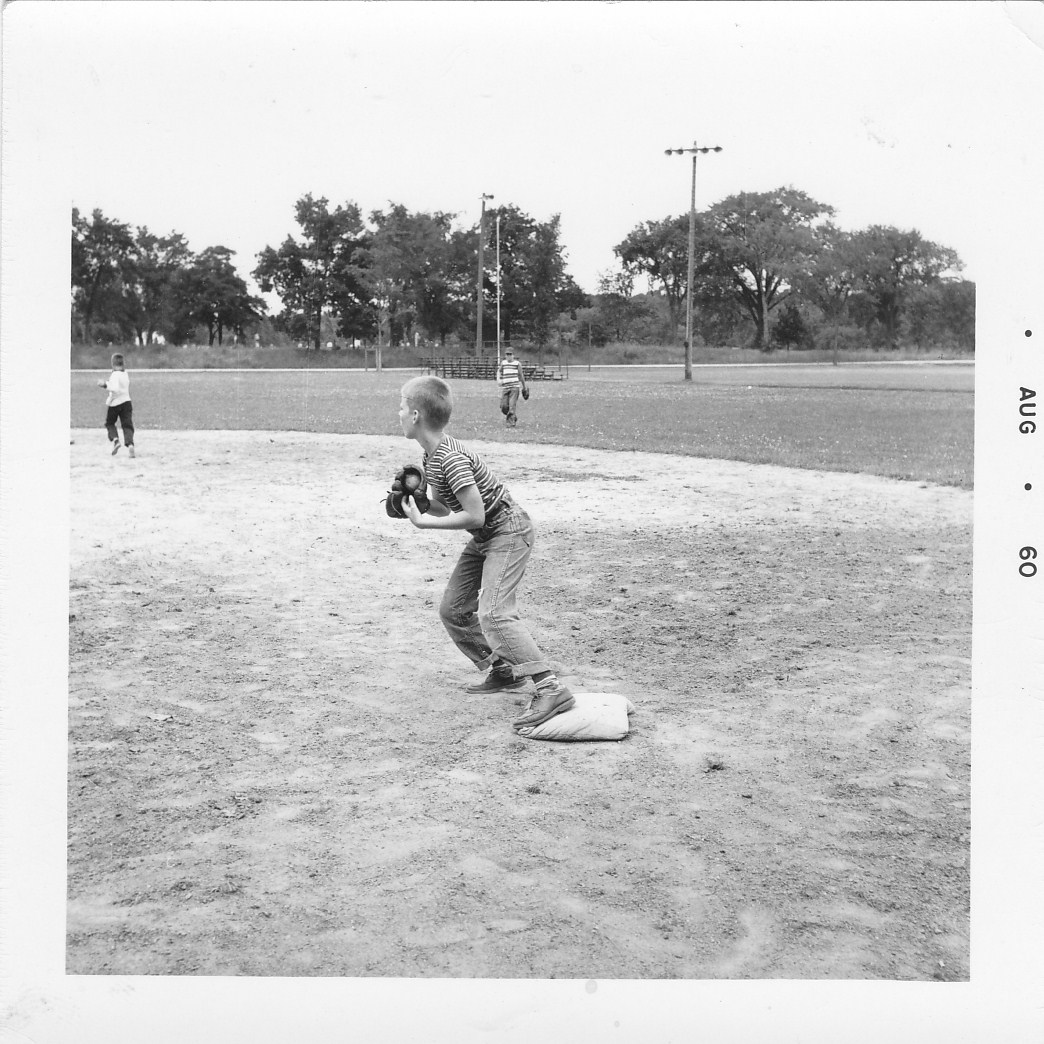

This isn’t my mom—though it sure looks like her. I have no photos of her playing ball; she was always behind the camera.

She had the best arm in the neighborhood. A quick, snap release with the ball cocked off her ear like a quarterback and a burn when it hit my glove. She’d played shortstop at the University of Minnesota during the war and even when I took the field in the late fifties she still had her infield range guns firing. I was a first baseman (left-handed and given no choice by the Pee Wee League coach) and we’d spend hours together practicing in the back yard driveway: me tossing grounders between the broken patches that marked the bases and her eating them up with a quick scoop, then the arm back and the forward blur. SMACK—another runner out.

She could hit too. Didn’t often try it in the yard due to constant use of clotheslines and the nearby overhang of a neighbor’s upper story, but when she did hit, it was line drives hard and nasty. I’d pitch (again my left-handedness exerting an automatic prod from the coach) and she’d come around on the ball with a grunt that warned me to get the glove up in a hurry. Never did see her pop one up, but then maybe my pitching wasn’t all that tough.

Life on the sandlot—note that I’m still wearing my school shoes. Mom understood the need to get to the field ASAP.

Nobody else in the neighborhood had a mother who played ball, but then nobody else had a mother who’d hitchhiked through Europe alone in the forties and could out-whistle the noon siren from the police station. When my mom played, she played hard. And when she couldn’t play, she cheered us kids on. If you attended any of my Little League games you knew her. She was the small woman with the unpermed hair and the down-at-heel shoes who sat in the first row of the bleachers and shouted like the Furies whenever I got a hit or made a catch at first. I never had an at-bat without hearing her voice come over the background hum of “heybatterbatterhey” and drop inside my ear with a “Come on, son!” or “Go get ‘em, Danny!” Always cheered at the right things too, not just the flash and overkill.

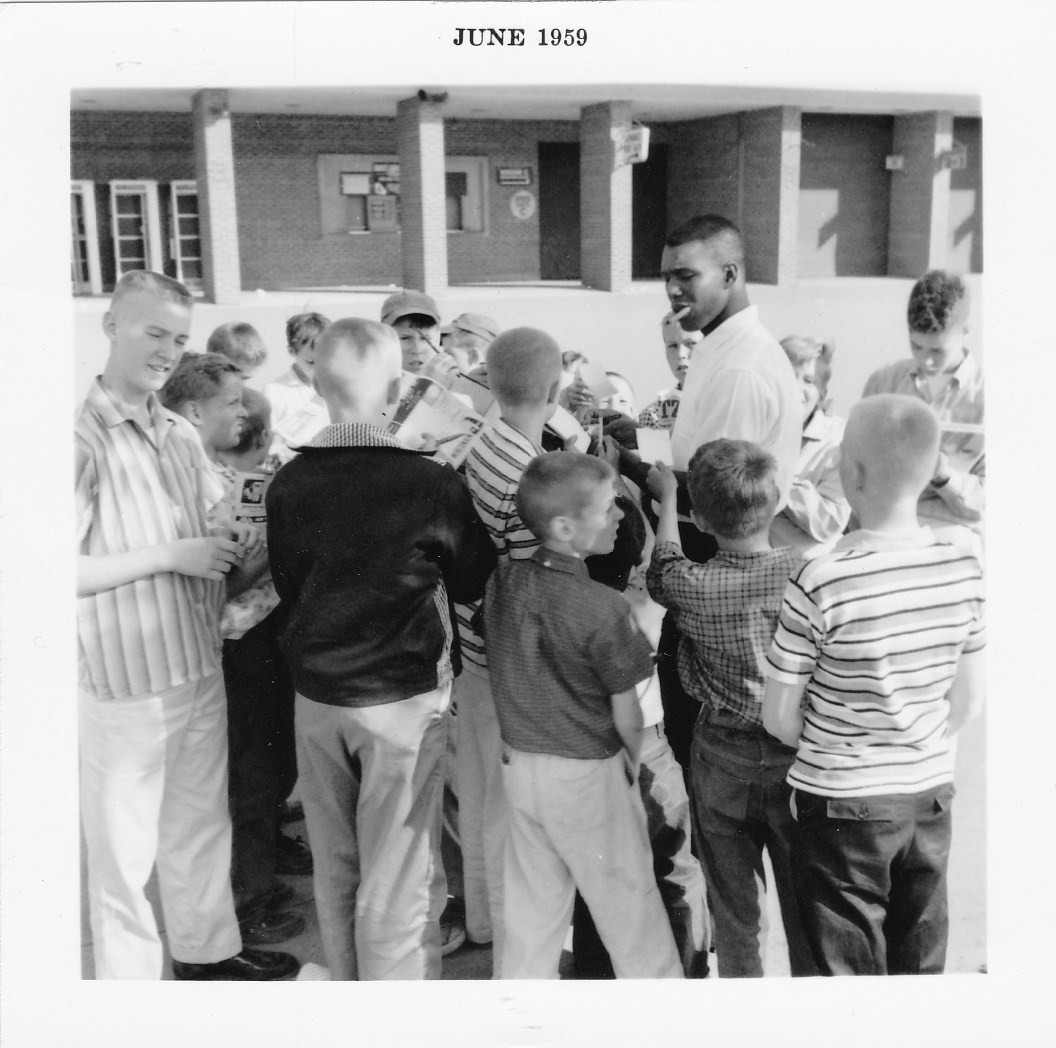

Other parents got too busy to come to the games, or couldn’t offer anybody rides home. Not my mom. It was line them up, stuff them in the back seat and deliver them anywhere requested. She only had five of her own. What were a few more shrieking voices or sticky fingers on the door handles? She took us out to major league games too, foregoing pork chops or a new secondhand coat to pay for the gas to Milwaukee and back. We even got to wait around after the games for autographs and I still have a photo that shows Wes Covington (smoking a cigar the size of a Little League bat) signing for our gang and me there on the fringe, caught between watching the Braves’ left fielder and my mom behind the camera lens.

After a Braves’ game, angling to get near Wes Covington. I’m center of the back row here, looking off to the side. (“Maybe Hank Aaron will come out next . . .”)

Maybe that split-sided glance is just how the memory ought to stay, because if there was one single serum responsible for injecting me with a double dose of baseball fever, it was my mom and her own rabid joy, not just in the game, but in the effect it had on me.

From my first feeble swings with a taped-up twenty-inch bat (“When you’d hit the ball,” she’s told me, “the bat would fly one way, your cap would go another and you’d run off in a third, to go sliding into the clothesline pole.” to the night in Babe Ruth League when I became the first player in two years to hit a ball into Lake Minnetonka, she was always there. Never riding me, just cheering me on. And as I watched her knees give and her arm go flat—the shoulder stiffening until she could no longer lift the ball above it—I knew there was no room for sadness at what had once been between us. It wasn’t something that had died, it had been passed on.

Thanks, Mom, for not making me come home from school and change my clothes before I hit the diamond. Who could stand to wait? The game was in progress. But you’d be there waiting when I pedaled up in the soft dusk of evening, racing the darkness home for supper. Beat-out sneakers and grass-stained jeans . . . A mud smear under my eye . . . The breathless nine-year-old retelling the bottom of the 7th with both the Pringle twins on base and Haago hitting a smash to first . . .

In the games we played together, losses didn’t count. I’ll remember that when my own time comes. And I promise never to smoke a cigar the size of Wes Covington’s.

Originally published in Minneapolis Review of Baseball, Vol. 8 No. 2, Spring 1989.