3 September 2016

The original concert review, never published:

Sunday, 17 January 1982

Half a dozen young men in twenties’ gangster suits and Russian peasant garb are onstage blowing their way through a hotblooded tune about “The Wild Women of Besserabia.” Several of them dance as they play, punctuating staccato passages with shouts of “Hey!” and upthrust arms.

At times they sound like a Polish wedding party. At others, like a New Orleans brass band. The music weaves sinuous rhythms around unorthodox tonality. The effect is at once joyous and plaintive. But what is it that we’re listening to?

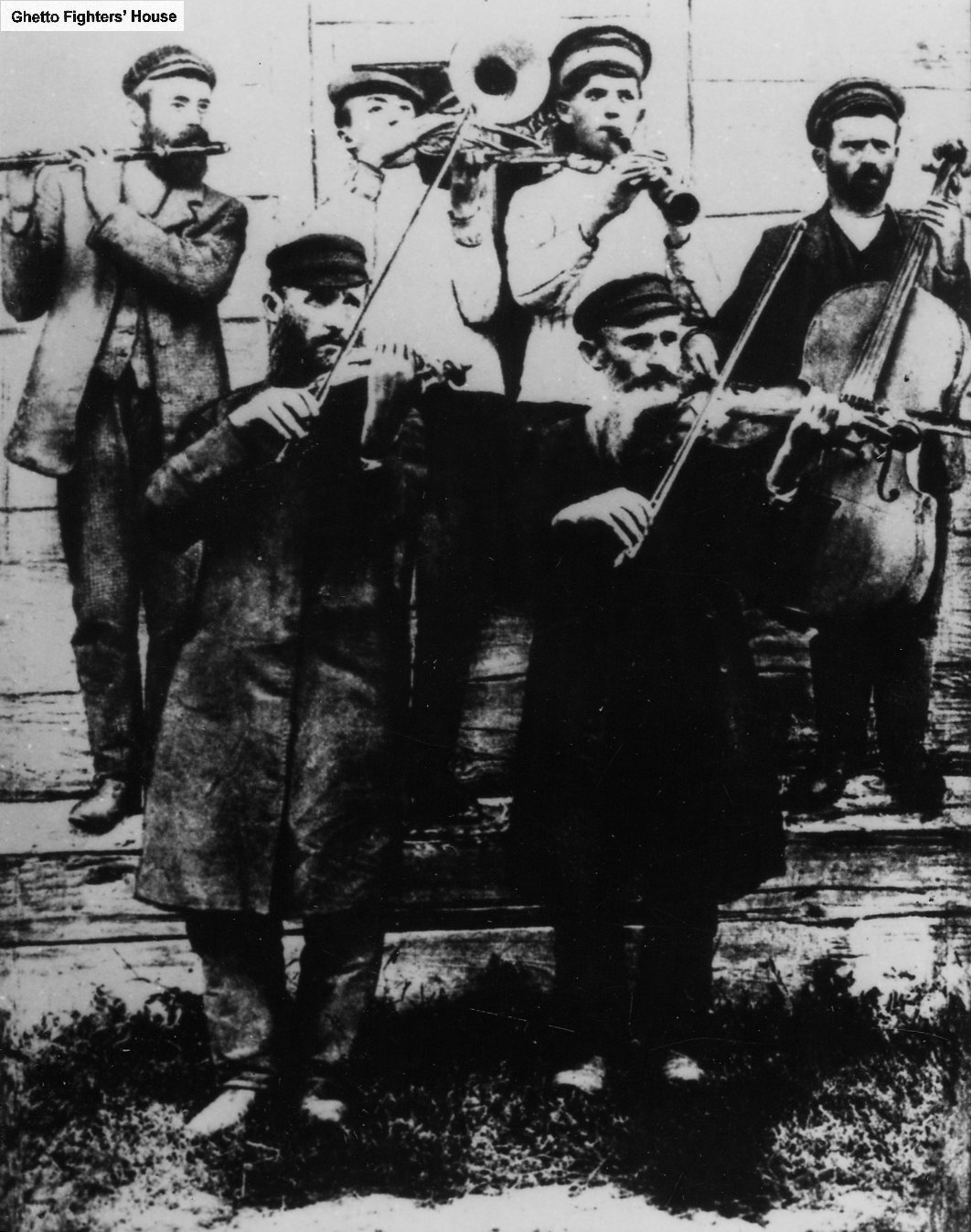

The short answer is Eastern European folk jazz as played by the San Francisco-based Klezmorim. The long answer takes us back three hundred years and across two continents. Klezmorim is a Yiddish word for itinerant Jewish musicians who wandered the streets of Eastern European cities from the 16th century on, playing weddings, feasts and sleazy bars. Somewhere near the end of the last century they exchanged their traditional violins for tubas, trombones, clarinets and xylophones. The result was klezmer music.

It came to America with the immigrants and thrived during the early decades of this century. Vaudeville, ragtime, jazz: all influenced and were influenced by klezmer music. It was an exciting time, but it was not to last. Young Jewish musicians like Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman, who’d grown up listening to klezmer, turned to jazz as a music that offered the same soulfulness and improvisational opportunities (without, perhaps, the Old World stigma attached).

It is a measure of the quality of the Klezmorim’s stage presentation that I was able to learn all of the above information while listening to a 90 minute concert of complex, dance-inducing music. The band knows its material—and its roots. Brief comments between songs and occasional dramatizations of real situations faced by the original klezmorim (e.g. a twenties’ recording studio enactment of a klezmer band recreating the music for a week-long Old World wedding in three minutes and 45 seconds) successfully updated the tradition and informed the uninitiated.

Musically, there was an intriguing mixture of classic jazz and Yiddish folk tradition. Tuba and trombone provided bass and rhythmic colorations in a strongly Old World style. The trumpet was moody and sparse. But when the clarinet and the soprano sax got going, it was New Orleans, here we come. Their lilting interweavings recalled the classic Mezzrow-Bechet recordings of the twenties and thirties.

The band’s founders—David Julian Gray and Lev Liberman (who performed the above-mentioned clarinet/sax duets)—showed the depth of their research in the breadth of material performed. The songs ranged from an 1886 football fight song to 1920s cartoon soundtracks.

Yet beneath the diversity was a unity—a kind of Jewish soul, if you will. There was an unkind irony in what a band member described as “essentially a dance music for hot-blooded youth” being performed for a middle-aged (though admittedly Jewish) audience in the subdued elegance of Pasadena’s Ambassador Auditorium. The band enticed us towards the atmosphere of the Yiddish feast and the low-life bar. We preferred the safety of our chairs. But we couldn’t keep our toes from tapping.