20 April 2016

Many thanks to the Excelsior-Lake Minnetonka Historical Society, for once again hosting an event that allowed me to revisit my misguided youth. Here’s how they billed last week’s affair:

Join us for a night about Minnesota Rock and Roll in the 1960s. Rick Shefchik, author of Everybody’s Heard About the Bird: the True Story of 1960s Rock N Roll in Minnesota, will be joined by Daniel Gabriel, who spent much of his youth in Excelsior, has written extensively on the Dance Hall scene, and completed a yet-unpublished novel inspired by Excelsior. They will recall a time when music was regional, when local dance halls catapulted Twin City bands to a national stage, and when Excelsior was among the region’s most important venues for new music.

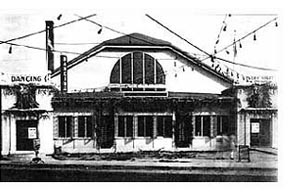

[Shown above is Excelsior’s Danceland, one of the biggest and most influential dance halls in the Twin Cities. Dig those entrance doors. From the look of them, they were stolen from the Amusement Park’s Fun House right across the street.]

I had never met Rick Shefchik, though thanks to a timely Christmas gift from son Alex, I’d been able to devour his book, which I loved. Rick and I seemed to hit it off quite well. I was told later that our sharing of the mic appeared seamless and well-rehearsed. Probably it was just our joint passion for the subject.

Rick emphasized some of the key bands of the era, offering historic photos

(everything from early St. Paul rocker Augie Garcia cavorting onstage in his trademark Bermuda shorts, to Danceland’s owner, Big Reggie Colihan, leaning in on 3 guys named John, Paul & George). His choices were excellent, though I couldn’t resist upbraiding him about underselling my favorite local band, TC Atlantic. (He did mention their single “Mona,” but I felt the need to bang the gong for “Faces,” an early garage band/psychedelic classic.)

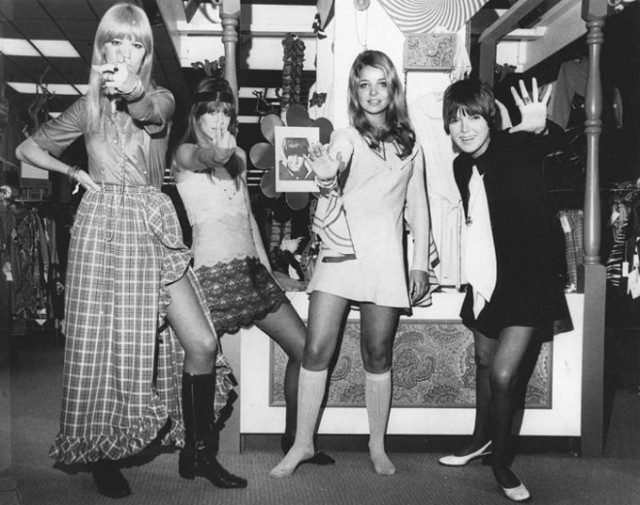

My angle was more about dance hall culture, and the rapid style changes that flitted past during the ’60s. From Continental style (greased-back hair and tight pegged pants) into the Baldie look (high-water pants worn with knee-length sox and spit-shined wingtips or shells) and so on to Mod (or at least the watered-down US version, which often mistook flair and exotic cut for the more subtle over-elaboration used by the early Brit Mods) and eventually the visual riot of Psychedelia. Women in the crowd helped fill in the many gaps in my memory about how girls’ styles vamped and changed. (Culottes, flirt skirts, hiphuggers and minis . . .)

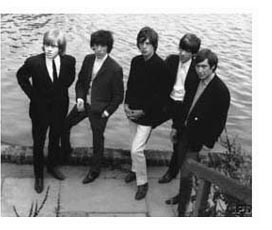

The crowd, once again, was incredibly knowledgeable—and standing room only. When Rick struggled to remember the name of an obscure ballroom in Pipestone (the far SW corner of the state), somebody in the crowd immediately piped up with the name. And when we discussed, inevitably, the legendary Rolling Stones concert at Danceland in 1964, no fewer than four people in the audience had been there. Memories? “All I could think of was how big the singer’s lips were” . . . “the bass player was holding his bass real funny, almost upright” . . . “I didn’t think the songs they played were all that different from local bands” . . . “Is it true what they say about Danceland and Mr. Jimmy?”

Ah, yes, Mr. Jimmy. Excelsior legend and supposed inspiration for the Stones’ “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” I won’t take the time to recount the entire story here, but I have come to realize that I am now considered an authority on the matter. Rick even said I had swayed his opinion from doubtful to possible. And, again, members of the audience had their own twigs to throw on the fire: “My friend worked the Bacon Drug soda fountain in those years, and she witnessed the encounter between Jagger and Mr. Jimmy.” . . . “I was one of Jimmy’s best friends. He talked about that time a lot . . .”

And afterwards, the stories kept on coming. One audience member after another had a memory to share. We could argue over which dance hall was the best, but we all agreed on what good times had been had. To quote Bunny Wailer, from a completely different context: “Rule Dance Hall!”