5 December 2016

Saturday night in the Alfama, Lisbon’s old Moorish quarter, with a half moon winking behind sporadic cloud cover, and faint smell of fish floating up from the Tagus River estuary. Wind gusts shiver down the back lane corridors. Alfama’s lanes twist and climb the hillside like petrified snakes named Beco (used for alleys or cul-de-sacs), Travessa (bystreets) and Calcada (ascending/descending roads).

Knots of couples and celebratory parties pull together, then move apart, drifting these streets (to quote Tom Waits), “looking for the heart of Saturday night.” A bottle is raised, a challenge proposed, on they go. The souvenir shops have all shut, but tiny mercados and an occasional café still stand open, hoping for one final customer.

Alfama backstreets wind up and down the hillside. At the top, the Castelo de Sao Jorge looms over the highest of Lisbon’s seven hills. Here comes a tram, still packed to the riggings and clanging its way up, down, and around the repeated bends. Any tramstop offers a tantalizing trail to follow, but we are searching particularly for casas de fados, the storefront “fado houses” run by fadistas, singers of Portugal’s national music.

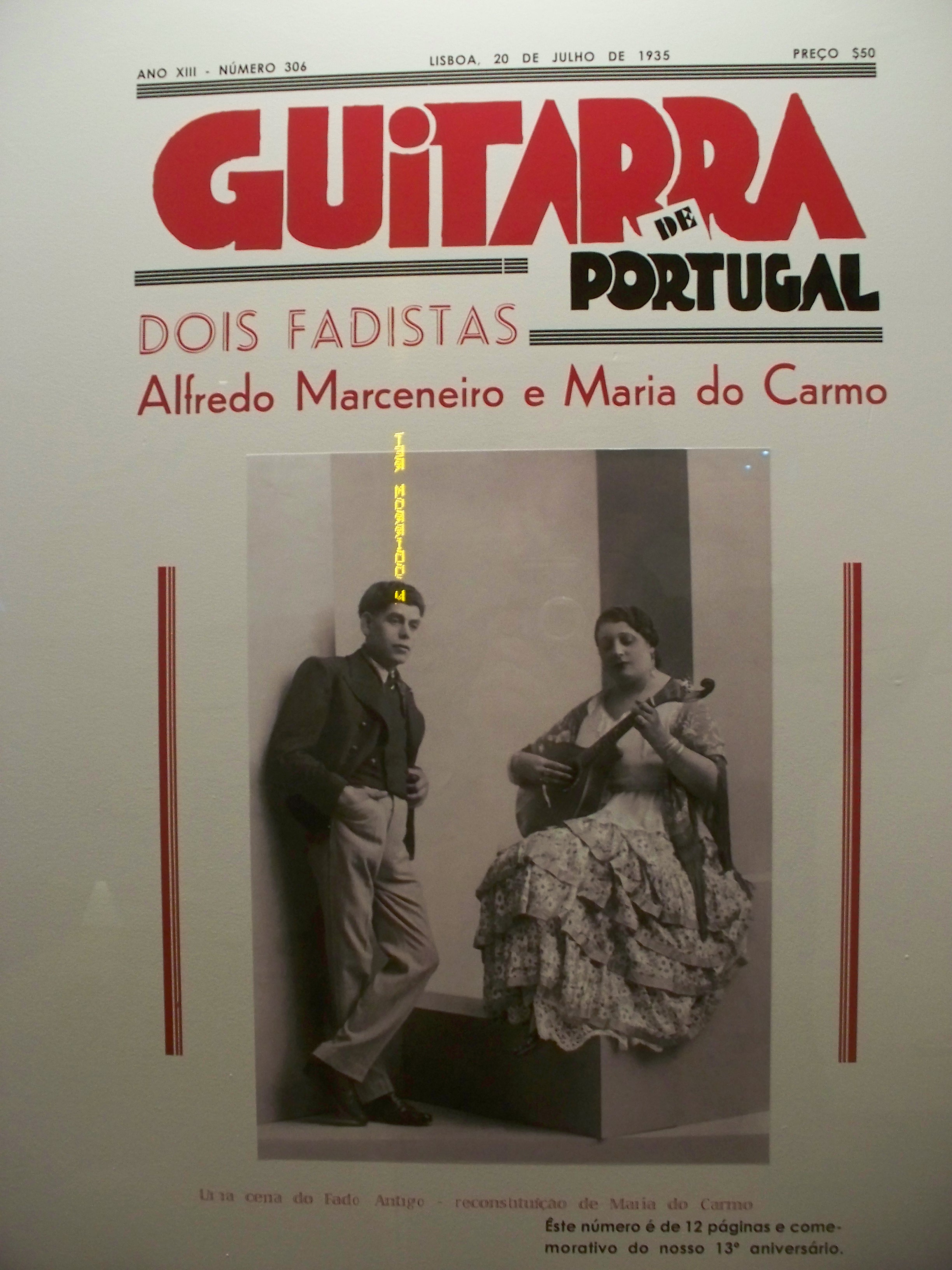

We find one on a bend near an 18th century church. The doors are open, and patrons sit at tables on an outdoor patio, with a blazing fire warming their center. The fadista (male, in this case) is standing in the doorway, singing to the crowd both inside and out, his hand resting on the shoulder of his viola player, with the soloist (on 12-string Portuguese guitarra) tucked out of sight inside the inner room. The soul-wrung sounds drift through the night air, over to our cold marble seats on the church plaza. Time to dip into our hip flasks and let the night air swirl with sounds.

After a bit, we wander another side lane, and hear more fado—this time a female voice—coming from behind a decorated door. We lurk outside, as do a couple of locals who are trying to decide whether this should be the spot to settle. The song rises, then falls, mournful notes drifting off into the star-sparkled sky. Fado means fate, and its dominant emotion, saudade, is an untranslatable concept that speaks of longing, and nostalgia—often a longing for something lost, or never obtainable. It is said to be the essence of the Portuguese character; embedded, perhaps during all those long, painful farewells between departing sailors and their homebound wives and loved ones.

We don’t speak enough Portuguese to truly understand the words, but there is no difficulty opening up to the emotion behind the songs. After the singer completes her traditional three-song set, we move along, meandering with the night, listening for sound wisps wending their way down the tangled lanes and alleyways. A cat crosses our path, and another one hisses from curbside.

Bursts of sound follow the opening of doors, and we let the mood rustle past as we pause. Our hip flasks stay busy. Now we’ve found a particularly rich singer, and linger long outside the door where she sings. The room inside is full to the brim, and others join us outside, waiting for departures in hopes of finding a seat. A taxi lingers, and is scooped up.

A young man rides up on a bicycle with a long black case strung over his back. Another guitarist . . . He hustles inside. Across the street an East Indian shop keeps its lights burning, and random loners cluster nearby, dipping into the shop for cigarettes, snacks, a beer or two. Nobody appears to know each other, but we’re beginning to form a community here on the doorstep. Even with the door shut, we hear the fadista’s wail.

In the city of Evora, Bota Alta is the prime casa de fados, and Ines Villa-Lobos the featured singer.

Then the set ends, and as a few patrons depart, the waiting souls outside begin to edge their way in. Jude spots an empty place near the back wall and we try to claim seats. There is a quiet brouhaha over whose seats these are, and whether leaving to have a cigarette means they are coming back, and eventually the whole scene gets so testy that we opt to withdraw into the streets instead.

Moments later, a rain cloud bursts and we hide beneath awnings and archways as we trudge wetly back to our tiny upper room apartment. We’ve left the skylights open, and already sections of the rooms are drenched. Heaven knows what state of affairs we would have eventually found had we chosen to stay and fight for those contested seats in the casa de fado. As it is, the memory of those slow, mournful sounds stays with us, coloring the night sky, and sending us off towards morning.