10 September 2014

Summer travels were brief this year, but a ferry excursion across Lake Michigan and thence up the lake’s eastern side offered an unexpected dip into history, and some intriguing night excursions.

The three huge “upper” Great Lakes—Superior, Michigan, Huron—all come together near the Straits of Mackinac (Superior is actually a bit north). The Straits separate the Upper and Lower Peninsulas of the state of Michigan, as well as dividing Lakes Michigan and Huron. Until the enormous suspension bridge was built in 1959, ferries connected the peninsulas.

Today, those fleeing Detroit and the other southern Michigan cities can speed over the Straits on a toll road and head for Canada. But a more interesting option is to put in at either St. Ignace (on the UP), or Mackinaw City (yes, the city spells its name that way even though the island and the straits do not) and grab a 20 minute ferry ride out into Lake Huron and lost-in-time Mackinac Island.

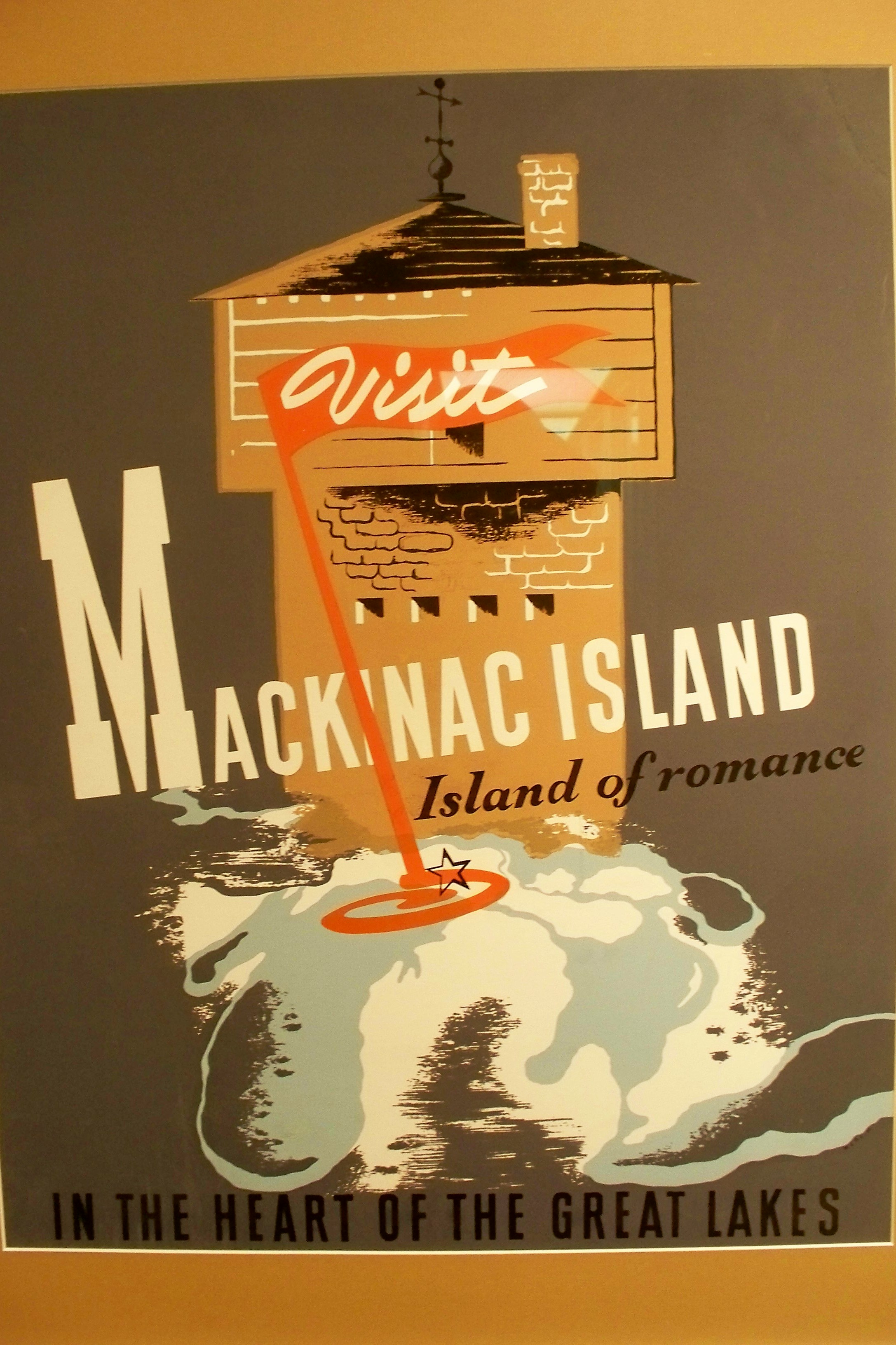

This classic 50’s poster spotlights (inaccurately) the island’s location in the middle of the Great Lakes.

Most of the island is a National Park and has been since 1875. The remaining section features 19th century vacation cottages, hotels, boarding houses and the like. Automobiles were banned almost as soon as they appeared on the island, back at the dawn of the 20th century. They scared the horses, and one thing that remains evident about Mackinac Island is that a working “horse culture” remains extant. Big-footed drays haul the islanders’ supplies off the ferries, serve as mobile amusement ride for carriages of visitors, thrill novice riders as they tromp along the high woods paths of the island’s interior . . . and offer the UPS man a seat on a hay bale as he delivers his packages.

The only rival to the horses are the masses of rental bikes that visitors use to tool around the backstreets of town, or out on the island byways. It all makes for a delightful pace of life. We rented a tandem and circumnavigated the island, using Highway 185—the only highway in the USA where cars are forbidden.

Highway 185 circles Mackinac Island. The easy 8 mile journey offers access to the tougher roads of the interior as well.

The centerpiece of the island, in many people’s minds, is the vast and magnificent Grand Hotel. Given that it costs $10 just to be allowed on the grounds, and even tea runs $30/person, we opted to view its splendor from afar.

To us, the real centerpiece is Fort Mackinac, set on the bluff overlooking the harbor. The fort was built in the 1790’s, which is when the US finally took possession of the island from the British. The gun towers still command the harbor, with views stretching off to the mainland, and the long, gallant line of the Mackinac Bridge. But unlike so many other US forts, this one did see battle. In fact, the very first battle of the War of 1812 was fought over the island. British forces on a nearby island learned of the outbreak of war before any of the American population did. The British sneaked onto the northern end of Mackinac, and advanced on the fort from its rear, less defensible position. Vastly outnumbered, the US garrison surrendered, and the island remained in British possession throughout the war. It was finally returned to the US as part of the peace treaty process.

We stayed east of the Harbor, in the shadow of St. Anne’s church, and one night were treated to hours of vibrant, swaying Pentecostal choir singing. It dawned on us that the singers were part of the hidden population of summer labor. Tucked into sagging boarding houses along side streets are hundreds of young workers from around the globe. We encountered folks from other parts of the US, from Europe, Latin America, Asia—and most of all, Jamaica. It all made for quite a lively scene after dark. Easy to imagine the bonds being built over the course of a summer.

Similar bonds seemed to exist among many of our fellow visitors. We were struck by how many couples we encountered visit the island on a regular basis, extending their earlier memories and revisiting familiar haunts. That’s hardly our style, but one could do much worse than spend more lazy afternoons sitting on the garden verandah of Haan’s 1830 Inn, watching the cyclists head off to Arch Rock and contemplating the dining options ahead.