3 February 2016

The low swirl of Waterland is as much a part of the sea as land. For birds, it’s a paradise.

For all the talk about the cutting edge “green living movement,” it can be instructive to realize that not everything needs to be re-invented. Many eco-friendly approaches to life can be found from poking around in the past—and present. During a jaunt to Noord Holland, I spent a day biking through the polders and wind farms of the area known as Waterland, which lies just east from Amsterdam.

My trip started at Amsterdam’s Centraal Station, where I dropped into MacBike, located along the southern end of the main building. I got a bright red pushbike, with a wide, comfortable seat, upright handlebars, and foot brakes. It was like riding a bike from my childhood—and best of all, it was instantly comfortable.

Being the Netherlands, there was a bike path starting right outside the door. Around the back of the station I went, where I cruised to a stop at a ferry crossing. Five minutes later, the free ferry had dumped me in Noord Amsterdam, where winding residential streets soon led to the heavy foliage of a city park and, beyond it, a bike path atop a dyke. In no time I was in open countryside . . . and then the gabled village of Schellingwoude . . . and then more open land along the dyke.

A boat, a canal, and a bike. Let the road stretch on forever.

This was a pattern that would repeat across much of the landscape. As far as the eye could see were polders and canals and dykes. All man-made. Even the IJsselmeer—the vast inland lake—was manmade, created by the Dutch in 1932 when they completed the great Barrier Dyke that closed out the North Sea and transformed the Zuider Zee and its fishing communities into the recreational IJsselmeer.

One could argue that this is the opposite of accommodating culture to the environment, but through hard, persistent work and the taming of the elements of wind and water, the Dutch have created quite a sustainable lifestyle for the inhabitants. Everything is on a human scale, with cozy villages and farms and houses linked to the single road by skiff platforms used to cross the tiny canals from one’s front doorstep. Clusters of cows and sheep nibble contentedly, and herons hunt in the shallows. Waterland is five meters below sea level—and still sinking. The moist grasslands serve as breeding grounds for many species of birds.

The further out in Waterland I went, the fewer villages there were. Even cars were scarce on the little road that sometimes paralleled my dyke path. I rode along above the water, self-propelled, and happy to leave a very light footprint. When bike paths diverged (and there were many such paths) signposts were quick to show the way. Even so, I took the opportunity to engage the occasional passing stranger in conversation, sometimes feigning ignorance just as a chat-starter. The only times I had trouble being understood were when I attempted to speak Dutch. English worked just fine.

But soon I had left the little villages, and only an occasional farmstead broke the horizon above the long, low canals and grasslands. Atop the polder the wind blew steadily, with the salt smell of sea air, and on my right, away from the farmlands, the IJsselmeer sprinkled whitecaps and cresting gulls glided against a slate grey sky.

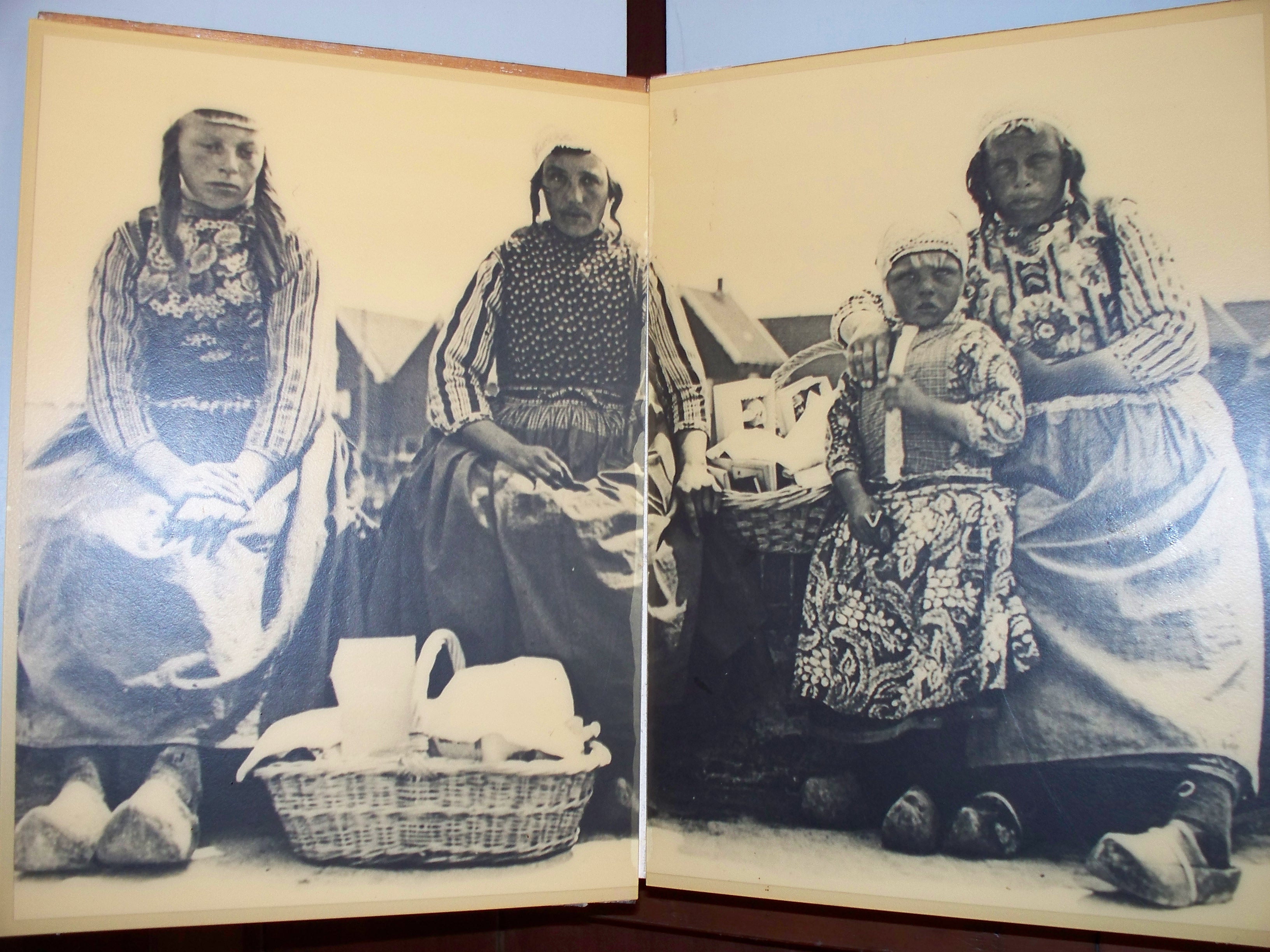

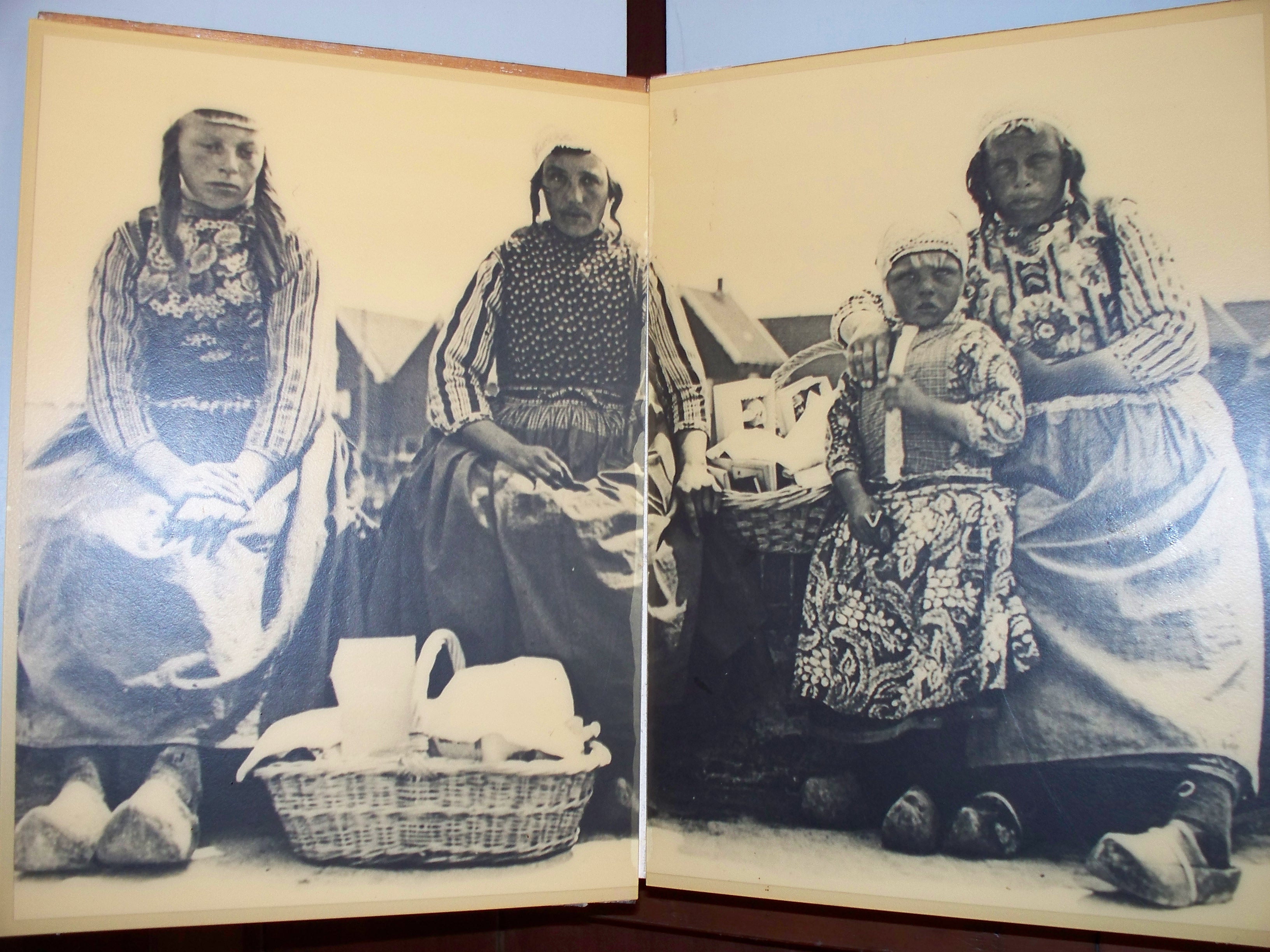

My goal since I’d set out was to ride all the way to Marken, a former island in the Zuider Zee which was now connected to the mainland by a causeway. Back in the early fifties, when Marken was still an isolated island outpost—and I was a wee toddler—I had traveled here with my parents. For years I’d heard stories from them recalling the little Dutch villages along the Zee, like Edam and Volendam, with locals in fulsome dresses and starched white caps, the men with their pipes and billowing trousers. Marken had particularly stood out, both as an end-of-the-road destination and because the local population seemed to have intermarried a few times too many for their own good. What would it be like today?

For centuries, the Marken folks were known for their distinctive dress and dedication to their fishing fleet.

Then I was onto the causeway. The winds whipped across my path. On the far side I dipped down through a quiet crossroads of bike paths and along a lane on the edge of town. The characteristic green-and-white wooden stripes of Marken houses huddled comfortably along canals, and bright banners with royal portraits heralded the 50th anniversary of the coming of the causeway. The narrow streets were tidy and quiet, the only sound the occasional clopping of shoes as locals strolled past. They certainly looked normal to me. I slipped along in silence, heading for the old Marken harbor.

Another dyke path pulled me on towards the mast and furled sails of pleasure boats tied up in a line along the breakwater. Four traditional houses stood in a row at the end, just as the old photos had portended. One featured espresso and pastries, and I gathered myself in the lee of a pair of outdoor tables and celebrated my return to the scene of yet another childhood memory.

Placid Marken Harbour has survived many a gale blowing in off the North Sea. Today it’s weekend sailors rather than true grit fishermen who call it home port.

It was mid-autumn and the sailing season nearly done. An occasional seafarer would ramble along the line of the boats rocking at anchor and hop aboard, tidying up and tucking items away. Two boys in Ajax shirts dodged in and out of the bollards along the harbor wall, playing an imaginary game of soccer.

I could feel the day sliding off towards evening too, so I gathered up my bright red bike, made a quick circle of the outer village and set off back across the causeway. I was twenty-some kilometers from central Amsterdam, with the promise of the other half of the cycling loop yet to be fulfilled.

Once back on the mainland, I passed a set of modern slim-line windmills, their pale grey poles almost disappearing into the equally grey sky behind them. I followed the coast for a few kilometers and then turned inland, winding down lanes and pasturelands that left the sea feeling remarkably distant. In Zuiderwoude and Broek in Waterland, gabled wooden houses were sprinkled along the roadside, and a cluster of red-lettered signs pointed the way on bike paths in all directions. The steeples of 17th century Dutch Reformed churches were the highest points in the landscape, and as the afternoon mellowed into early evening, I settled back in a slow, comfortable riding rhythm.

Bike paths in Holland are thick on the ground, and often more convenient than driving anyway.

I crossed over the Noordhollandsch Kanaal on a high bridge, dodging a moment of traffic, and then looped down through woods and parkland that paralleled the flowing water. Above me on the far bank the rush of traffic multiplied until it seemed a motorway of frantic visitors heading for the center. Yet my path continued to wind through trees, past dog-walkers and couples strolling hand-in-hand. An old-style windmill appeared in my track, its wide sails stopped forever, but still a symbol of the old ways.

Ahead I could see the ferry landing, and across the Het IJ the sprawling edifice of Amsterdam Centraal Station. Was it really still the same day as when I’d left? I felt I’d traveled much further in time even than in distance, and that in some important ways I’d penetrated closer to the heart of the Dutch psyche.