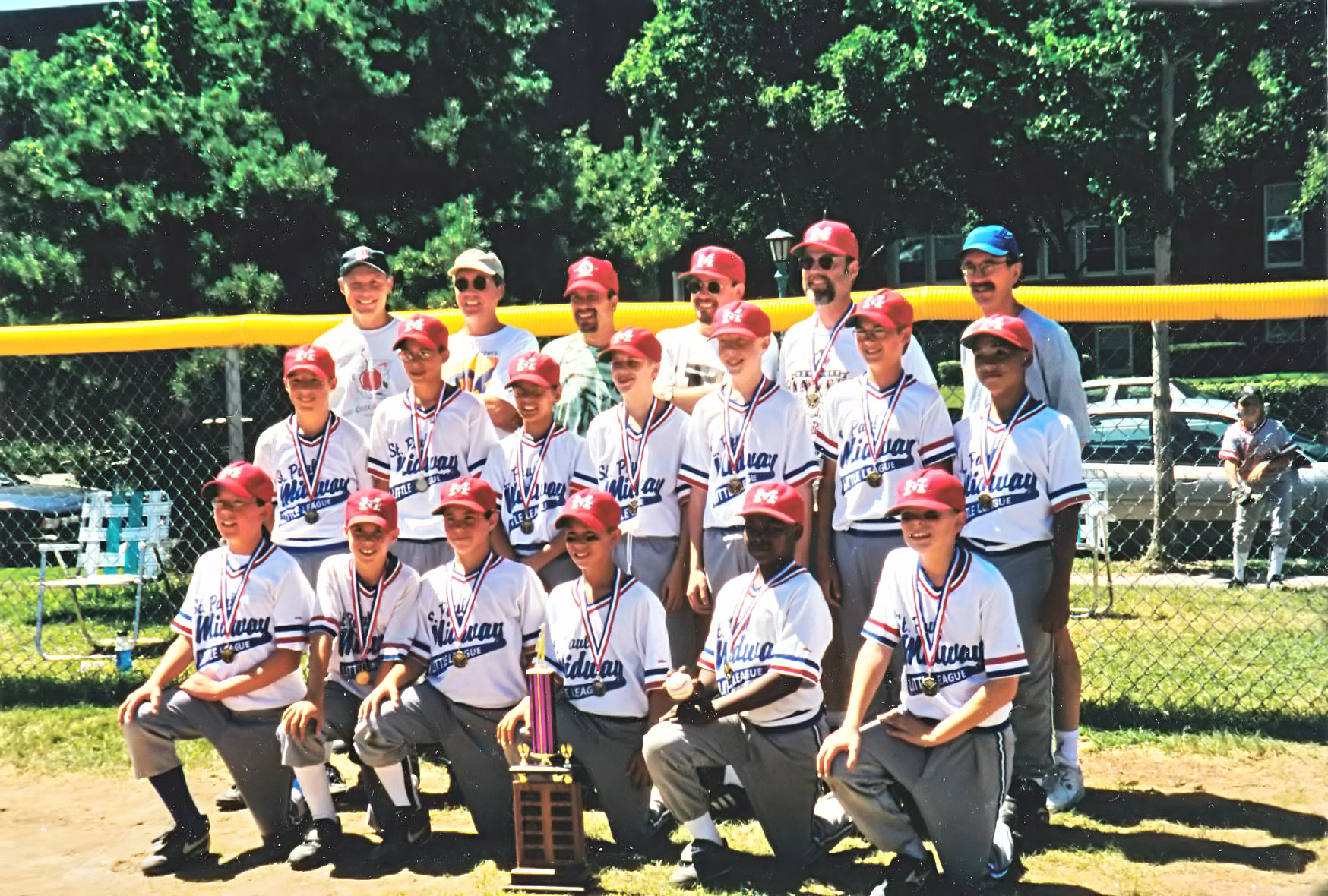

1999 M&L Yankees try to keep it together for a team photo. Front row: , L to R: Olajowun Edmunds, Will Lehman, Robbie Punch, Zak Prauer, Tyler Halva, Jonathon Kretman, Brian Spindler. Back row, L to R: Coach Stephen Lehman, Donovan McCain, Peter Oleson, Jimmy Shoemaker, Cole Woodward, Alex Gabriel, Thomas Van Geldern

13 August 2014

Even a year or two later, when the subject comes up, our left fielder Thomas’ dad is still saying, “Gotta be the wildest play in baseball I’ve ever seen.” And that next winter, when we appear unexpectedly to sign up for the Winter Dome League, the head coach greets us with, “Now we set. I can still see that play, man. Oh yeah—we gonna be fine at catcher.”

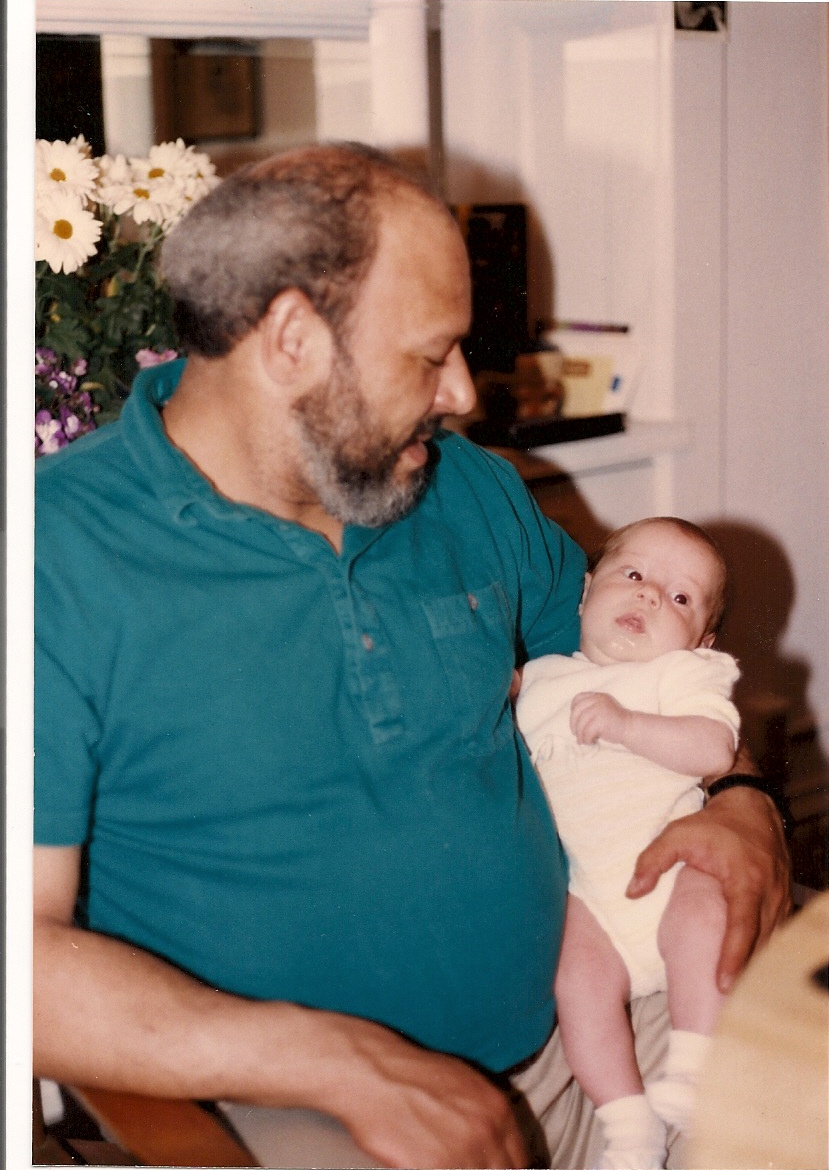

For Alex, my son, it marked the end of an era. He’d been playing ball in our local Little League—St. Paul-Midway—since he was seven years old, and the youngest kid in the league. I’d been his coach each year, up through the seasons of “coach-pitch” ball, then Double A with it’s “no stealing” rules and finally, the pinnacle of our league, Triple A ball.

Alex was the catcher, all the way, ever since he’d begged me back in that first year to let him put on the battered, over-sized shin guards and chest protector. I tried to tell him, “Whoever heard of a seven year-old catcher?” but the shine in his eyes made me relent. At first you could hardly see him underneath all the equipment, but bit by bit he fought his way along, handling wild pitches and high heat, balls in the dirt and base stealers gunning for third. By the time he was twelve, he was one of the two best catchers in the league. The other was Josh, whose dad also coached and, as a consequence, the two boys were rivals. Good-natured, respectful of each other, but rivals nonetheless.

Alex was well-satisfied with his Little League career. The only problem was that we’d never made it to the championship game. This was a big deal in our neighborhood. The Double A and Triple A championships were the centerpieces of the all-day Little League Carnival which was our season’s finale. To top it off, the games were televised live by our local cable TV company. Yet each year we found ourselves in the bleachers watching other teams slug it out for glory. Something was clearly missing.

Finally, in Alex’s twelve year-old season—his last year of eligibility—we managed to reach the championship. As the Yankees, we finished third in the league and then fought our way through a tough five game playoffs to come up against the mighty first place Orioles. At last! Our own chance at glory.

The Orioles were built around three players; the three J’s, we called them. Two were their pitchers—a pair of lefties named Justin and Jon. The other was Josh, that rival of Alex’s for best catcher around.

The game came down to the bottom of the 6th and final inning, with us up 2-0. We had our ten year-old phenom, Robbie, on the mound to close, but coming up was the top of the Orioles’ order. To further complicate matters, our right fielder had been hit by a fast ball in the leg in his last at-bat, and as he tried to run out onto the field he realized he couldn’t go. We pulled him in to the bench, sent out for ice packs, and began to scramble our lineup.

We kept ace defender Jimmy at second. Donovan came off the bench to play first, our first baseman Cole moved to short, and our shortstop, Willie, was sent out to a position he had never played—right field. Some people might wonder about this—why stick your shortstop in right, particularly if he’d never played there?—but it was his dad, Steve Lehman, my co-coach, who suggested it. Two of the Orioles’ Big Three were lefties; there might just be a key play in that direction.

M&L Yankees dig in (Cole Woodward at SS; Olajowun Edmunds at 3B; Thomas Van Geldern in LF) behind Robbie Punch. The white prison bulk of St. Paul Central High—where several team members later starred—looms in the background.

So with this jury-rigged lineup we hit the field. Right off the bat we got a grounder to short—a clean play by Cole and a good stretch by Donovan at first. One away—and already two of our position switches had been tested.

Up came Justin, who hit another hard smash to short. A repeat—except the ump claimed Donovan pulled his foot off the bag at first. Runner safe. Now Josh hit a rocket to left center for a single. Men on first and second, one out, and big Jon coming to the plate. Jon was the top home run hitter in the league and suddenly our 2-0 lead looked very precarious. If he went yard here, the game would be over.

Alex set up on the outside of the plate, away from Jon’s left-handed power, but when the pitch came in, Jon rocked it high and deep to right. That ball seemed to hang up there forever. If it cleared the fence, we’d lost. If Willie could catch it, the runners would be tagging and advancing. . . .

Every eye, every body bent forward, watching. And then—the ball dropped in fair along the far right field foul line, nearly at the fence. The runners exploded off their bases. Surely one run would score and quite possibly two, which would mean a tie game with big Jon still circling the bases.

But Willie picked the ball up and heaved it—an incredible heave—all the way in the air to our pitcher Robbie, who’d correctly moved to the midpoint between third and home, thinking he’d be the back-up if there was a throw to either base.

Amazingly, even Justin, who’d started from second, had to hold at third. Mentally, I was going, Wow! What a throw! And . . . OK, bases loaded, one out, now we’ve got to . . . when the fans erupted. Jon, who’d hit the ball, was racing towards second, sure that he’d get at least a double. But second base was already occupied.

Shouts from the stands—from both benches—from players on the field. Jon threw on the brakes halfway to second and began to retreat to first. Robbie, who’d been making sure the runner at third held, turned, double-pumped, then fired the ball to Donovan at first. Donovan threw down the tag just as Jon slid back in and they both went down in a heap.

The base ump signaled out (OK, I thought, that’s number two) and Donovan, tangled on the ground, held the ball aloft in his glove in triumph.

But the play wasn’t over. As soon as Robbie had fired to first, Josh’s dad, coaching third base for the Orioles, sent the runner in from third. He scored easily (2-1 now), with Alex standing just in front of the plate, screaming for the ball. Donovan didn’t see. He was still tangled up and still thrilled he’d held on and only now, when Josh, who’d started the play at first, and moved to second on the hit, was waved around third and on in to home, did Donovan begin to grasp that events were still transpiring.

Alex was jumping up and down, up and down, waving and yelling for the ball. But in one section of my mind, while I too yelled to Donovan (“Home! Throw home!”) I knew we’d blown it, it was too late, Josh was too fast to catch now.

And then, at last, Donovan struggled to his feet and fired home. Alex was set in perfect position, but I could see that even if he caught the ball cleanly and turned, as catchers always do, counter-clockwise back to the third base line to put down the tag, it would be too late.

The moment of the throw—between Donovan releasing and Alex catching—seemed a near eternity and, always, there was Josh pounding ever closer down the line.

Then, in an exploding instant, Alex pulled in the ball and whirled—not the usual way, but clockwise, twisting himself backwards to plant glove and ball directly on the front edge of the plate where Josh’s foot was just coming in on a slide. Ball down, foot hits, catcher holds on!

Umpire: “Yer outta there!”

Game over, we’re champs. The ballpark explodes and Alex, through it all, is leaping and jumping and twisting some more and holding on to that dang ball. Final play of his Little League career.

“Wildest play in baseball I’ve ever seen,” says Thomas’ dad.

This piece originally appeared in Elysian Fields Quarterly, Vol. 21 No. 4, 2004.

1999 Triple A Champs—the M&L Sports Yankees. What an array of coaching talent! (Jeff Prauer, Donovan McCain Sr., Roger Kretman, Stephen Lehman, Daniel Gabriel, Bill Shoemaker) Front row, L to R: Jimmy Shoemaker, Will Lehman, Robbie Punch, Zak Prauer, Olojowun Edmunds, Thomas Van Geldern. Second row, L to R: Alex Gabriel, Cole Woodward, Jonathon Kretman, Dane Nelson, Donovan McCain, Peter Oleson, Brian Spindler.