7 May 2013

Readers of Tales From the Tinker’s Dam, my collection of stories set in a Welsh country pub, may enjoy this excerpt from a piece I published a few years ago. It’s a portion of a faux-book review (purportedly, The Wonderment of Welsh: Lingua Franca for Ages Past and Future by Dr. K.F.C. Belugabrahmanyan), featuring any number of authentic geographical and linguistic details, but whose meanings are bent in an unusual direction by the effulgent Dr. B:

. . . Dr. B, whose original tongue is Tamil, postulates the existence of a pan-global proto-Brythonic snake of linguistic affinity stretching from Ireland in the west to the NIcobar Islands in the east. Besides Tamil and Welsh (which he considers to be the cornerstone of any such clustering), he finds tempting links between the now extinct Cornish, south Indian Telegu, ancient Etruscan, several of the more obscure languages of the Caucasus mountains, and the previously unclassifiable Burushaski. . . .

K.F.C.’s greatest contribution may be in his consideration of the commonalities of loan words from both Tamil and Welsh into English. Welsh, of course, has given us such household terms as “lickspittle,” “toasted-turnip,” and “ab yrs,” which is found in particular usage in the British Isles. Dr. B even goes so far as to say that the reversed V sign formed by the pointer and middle finger (so often used in accompaniment to the “ab yrs“) finds its original home in a similar Tamil gesture.

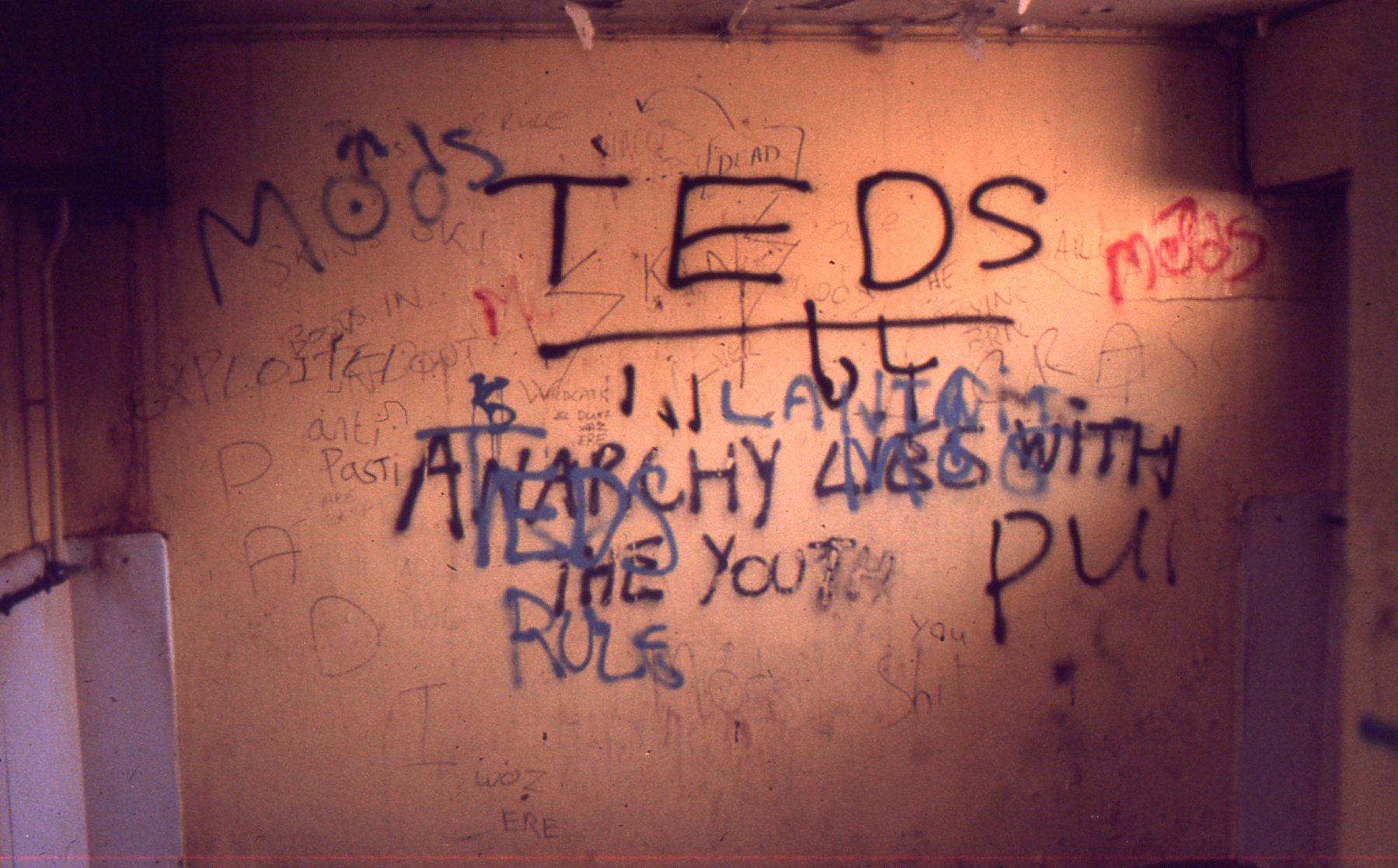

Dr. B credits the Welsh love of unhedged fields for this rare example of a cross-fertilized public loo featuring no fewer than three anarchic sub-cults. Mods (60s), Teddy Boys (50s) and Punks (70s) all find mention above the line of slash.

Completely new to me was Dr. B’s assessment of the impact of Tamil on English. Words such as “potato,” “forensic,” and “submarine” all come, it appears, from the language of his youth. Add in the Tamil origins of place names like “Berkshire” and “Weston-super-Mare” and one realizes with a shock that the dominant language of South India has been inflecting the British countryside for centuries!

For all my admiration of Dr. B’s fine work, he did appear, at times, to be stretching the cultural links between South Wales and South India. True, both areas represent the southerly region of their larger nations, but I was not fully persuaded that Rugby Union derived from the Juggernaut festival in Orissa. Rugby League, perhaps, but never Rugby Union. Similarly, his finding that the settlement pattern of the South Wales mining valleys exactly replicates that of the leatherworking pits along the Bay of Bengal seems to me coincidental.

Perhaps the most intriguing along this line of inquiry is his linkage of the explosive growth of the 19th century Methodist Chapel movement in Wales with the missionary outpourings of a handful of go-ahead Tamils building on the ancient church founded in India by the Apostle Thomas.

Dr. Belugabrahmanyan locates the initial influx of these missionaries at one of the most famous educational institutions of the Celtic church: St. Illtud’s sanctuary in Llanilltud Fawr, long a site of monastic learning. While St. Illtud’s is no longer, its theological imprint has been passed down to the White Monks of Cymer Abbey. (Dr. B believes this sect to have been derived from the White Jews of the Malabar Coast.) And, given that the daily gruel of the monks residing at Cymer Abbey is masala dhosa, washed down with palm wine, he would seem to be on to a significant discovery. He cements this linkage with the observation that the Welsh cheer “hiraeth, hiraeth, herein,” finds echo in Tamil’s “hiya, hiya, haroo,” though I suspect that the following line in Welsh (“Hale y tywalltai ei gwin iddynt,” i.e. “Liberally I poured the wine for them”), which he discovered carved into the Abbey’s gateway, may indicate a commonality of a more sensual nature.

At times, Dr. B’s ingenuity surprised even me . . . I was not aware, for instance, that the word “ffwl,” or “fool,” is found in seventeen languages between the Ross of Mull and the NIcobar sea ledge. Or, indeed, that the Welsh poet Huw Llwyd’s cry “Nid hawdd heddyw byw heb wad, Er a geir o wir gariad,” (“It’s not easy to live today, no denying, despite what there is of true love,” or, as some authorities have it, “Noddy has run off with my purse”) is found carved (albeit crudely) into the interior temple wall of the Mahabalipuram temple outside Madras.

I was also much taken with Dr. Belugabrahmanyan’s close analysis of random linguistic affinities, which demonstrate the long-time impact of the Celtic Brithonic languages on those of other tongues. As he points out, the Welsh word for water (dwr) is remarkably similar to that of other languages (cf. French l’eau, Spanish agua, or Burushaski bruuum). And, once he has drawn our attention to it, we can see quite easily the close correlation between the Welsh query “Pa bath ya geid I ohirian?” and its English counterpart “Why are we kept lingering?” . . .

Originally published in Bibliophilos, Fall/Winter 2007