22 October 2014

“Sha la la doo bee wah bum bum bum yip yip bum”

—background vocals on Roy Orbison’s “Blue Angel”

Roy Orbison contemplates how to tell the Teen Kings that he’s replacing them with a set of female singers who can actually get their lips around that tricky “Blue Angel” chant.

Say what?

How many times have you asked yourself, “What are those guys singing in the background?” I’m not just talking about supposed messages buried in the mix, though I’ve seen entire parties break up in an argument over whether or not the muffled sounds on “Revolution #9” heralded Paul’s death or the directions to the backstage area at the Isle of Wight Festival. I’m thinking of the secret thrill of suddenly catching the counter rhythm of The Who’s relentless fade-out chorus on “I Can See For Miles” and riding it across the airwaves like a steam train pounding through oblivion. I’m thinking of pre-teen nights in my grandparents’ parlor, soft-tuning the radio to forbidden rock ‘n’ roll and coming on the sweet, slick onomatopoeia of the backing singers on Bobby Day’s “Rockin Robin” going tweet, tweet, tweedileedeelee . . . tweedily deedily dee . . .

I know I wasn’t the only one out there earballing transistors for mumbled jive either. Phil Spector took a good close listen to the Shirelles’ “I Met Him on a Sunday” with its chorus of:

Do ronde ronde ronde

boppa do ronde ronde ronde

boppa doo . . . ooohhh

and found a way to play off those lines in his classic “Da Doo Ron Ron.” The Tokens must have huddled around many a jukebox pumping early East Coast group harmonies before they learned to use them for the A-wim a-away chant on “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.”

So what, you say? It still sounds like nonsense—and what’s that got to do with rock ‘n’ roll? Well, sometimes it’s nonsense. Sometimes it’s not. Since backing vocals never seem to get included on the lyric sheet the temptation is great to overlook them, but whether it’s the Cadillacs mouthing whop wah diddle it on “Speedo” or The Clash singing “I don’t want to die, I don’t want to kill” underneath “The Call Up,” those voices in the background are as important a part of the song’s effect as the bass patterns or the sax riffs.

For one thing, they provide vocal texture. And to the extent that rock ‘n’ roll embraces black music forms, it has always been built around vocal texture. You didn’t think the Beach Boys sold all those records because people fancied Mike Love’s whine, did you? Or think of the haunting background on Dr. John’s voodooized “Gris-Gris” (gris gris gumbo ya ya, hey now bumbo ya ya). The mood darkens, the fog rolls in, and spirits walk the night. Be it work songs, gospel choirs or Caribbean rhyming games, Afro-American music finds its deepest expression in the interweaving of human voices.

The appearance of background mouthings in rock ‘n’ roll springs from the close harmony “barbershop” style of singing that developed on New York street corners in the late forties and early fifties. Known to rock ‘n’ roll fans as Doo Wop, the style was popularized by groups who featured a wailing wordless melody behind the lead singer. The so-called “bird groups”—Orioles, Ravens, Robins, and the like—all used it well, but one of the most effective is the simple ba-dah-dah repetition on the Moonglows’ “Sincerely.” The Five Satins fueled many a curbside cuddle by taking this approach to extremes in the droning, moaning harmony chant behind “(I’ll Remember) In the Still of the Night.”

While backing vocals’ main contribution is often as a re-emphasis of a song’s immediate thrust, their role doesn’t need to be limited to that. On Ray Charles’ “Hit the Road, Jack,” the Raelettes break out of their presumed backing role to all but overwhelm poor Ray (an incisive parallel to the song’s theme). In similar fashion, I have yet to listen to Ike and Tina Turner’s “I Think It’s Gonna Work Out Fine” without getting goosebumps over the sly, sexy interchange between Tina baiting the hook and Ike dodging the lure (TINA: “They used to call you the Thriller . . .”; IKE: “The Killer, baby, the Killer . . .”)

And in Ike and Tina’s “A Fool in Love,” African call-and-response patterns are used in a moving dialogue between singer and chorus:

TINA: “Oh, there’s something on my mind; won’t somebody please, please tell me what’s wrong?”

IKETTES: “You’re just a fool, you know you’re in love.”

TINA: “What you say?”

IKETTES: “You got to make it to live by yourself . . .”

This passing on of an underlying message may be the most important role played by backing vocals. Outsiders can be mocked with impunity and insiders can giggle over retorts that sometimes undercut a song with hidden irony. Check out the mid-sixties Equals’ tune “Baby, Come Back.” (“Please don’t!” shouts someone in the background.)

This sly solidarity of in-the-know rockers can be found underlying many a song, but sometimes the implied joke doesn’t even reach insiders. The Beatles have been accused of hiding messages backwards and forwards in their songs, but the only one Paul McCartney admits to never even gets mentioned (the tit tit tit behind the verses of “Girl.”)

Some songs take things right over the top and elevate nonsense syllables to lead status, as in the Rivingtons’ “Papa-Oom-Mow-Mow,” which contains almost no real lyrics at all. Even that is taken to further extremes in what I like to think of as the very first “dub” version of a rock ‘n’ roll song—The Trashmen’s “Surfin’ Bird.”

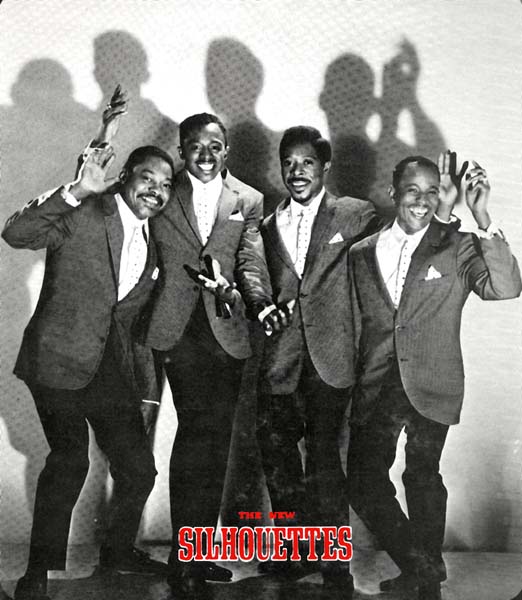

But even nonsense syllables can carry a symbolic content. One fine example of this is the Silhouettes’ “Get a Job”:

Yip yip yip yip yip yip

Sha na na na

Sha na na na na (repeated four times)

(ba doom)

Yip yip yip yip yip yip

Bum bum bum bum

Get a job . . .

Here we catch the parent’s nagging through the ears of the kid: just so much jive talking that always focuses on the final line—get a job.

In some ways, the use of nonsense syllables represents a core concept of rock ‘n’ roll: the need to hold on to the jungle; to the non-rational, nonlinear thought forms of an earlier, more gut-wrenching age. When the Showmen sing a repeating chorus (in “It Will Stand”) of “Rock ‘n’ roll will stand, scooby doo be doo,” there is a feeling that these two lines belong together. That so long as this kind of atavistic mindset remains in force (wherein scooby doo be doo is a legitimate response to the world) rock ‘n’ roll will indeed stand.

Perhaps this is something of what Barry Mann had in mind when he sang in “Who Put the Bomp?”:

Who put the bomp

In the bomp shoo bomp shoo bomp?

Who put the ram

in the ram-a-lama ding dong?

Who was that man?

I’d like to shake his hand.

He made my baby

fall in love with me.

What’s it matter who put the bomp? The important thing is, it’s there.

This article was previously published in One Shot, Vol. 2 Issue 1, Fall 1991 and The Northfield Magazine, Vol. 4 No. 4, 1991.