20 January 2014

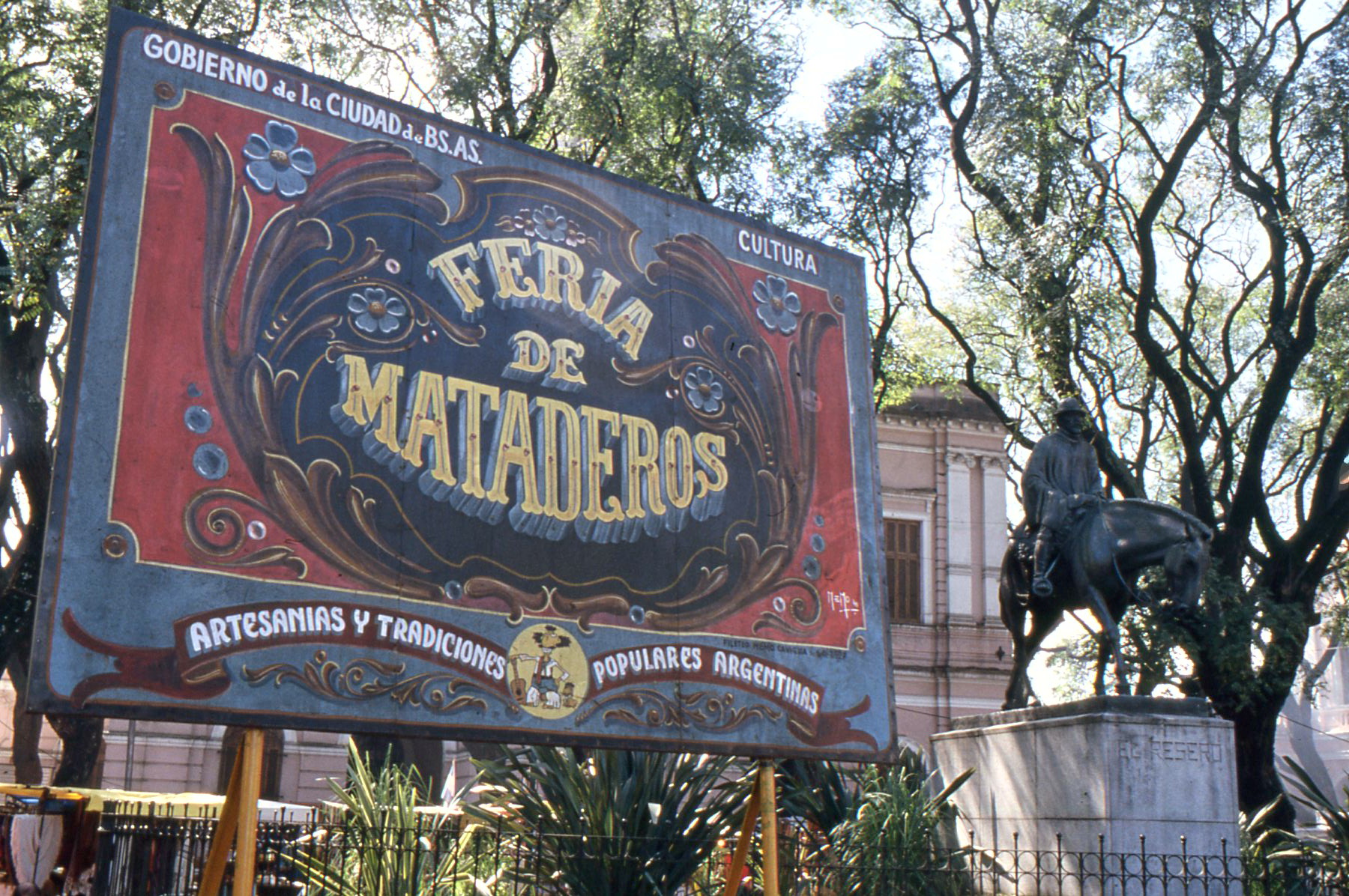

The crowd edges in, nearly touching the narrow, sanded raceway in the middle of the street. It’s time for the climax of the weekly Feria de Mataderos, here in a far-flung barrio of Buenos Aires. The dances, the drinks, the posturing and preparation are all put aside. Each rider has a chance to prove himself in the Carrera de la Sortija (Race of the Ring), a competition dating back to the Spanish conquistadores and still played on the pampas.

The horses paw, and the proud, dressed-to-the-nines gauchos make their final adjustments. Belts are resettled, hats tipped just a bit more jauntily. At the far end of the street, a signal is given, and the first horse and rider kick into action, pounding down the pavement with the crowd yelling and moving closer and the gaucho flicking his whip from side to side on the horse’s flanks, then standing high in the saddle at a full gallop. Ahead of him is an archway, with a single red rope dangling from the top of the arch. On the bottom of the rope is a tiny metal circle, perhaps twice the size of a wedding ring.

The gaucho’s task? To spear that metal ring on the end of his lancet—a small stick about the size of a pencil—while passing underneath at a full gallop. It requires a centaur-like creature, horse and rider working as a single body. The pace of the gallop is key: the fiercer the approach to the sortija, the more macho the rider.

When his horse is merely strides from the archway, the gaucho reaches along his hip, pulls out his lancet and raises it alongside his right ear, ready to strike. The horse thunders on, the gaucho stabs forward and . . . no, the rope trembles but the metal ring remains intact.

The crowd sags visibly. The gaucho turns, shrugs and trots back, head high, to retake his place in the line of waiting riders.

Now comes another and another, each one obeying the dynamics of the ride: horse at full speed, hands to the whip, then to the reins while standing, then to the lancet and, at last, the plunge.

On the first round, every rider tries and every rider fails. But now they’ve measured the course, settled their timing. While they wait to go again, the young gauchitos, will get a try.

First, a longer metal wire is put on the archway and the ring set low enough that the younger riders on their smaller horses can reach it. For the youngest ones (aged seven and up), merely staying on the horse and making any sort of stab with the lancet brings applause, sprinkled with laughter, from the crowd. The older youth, in their mid-teens, who are desperate to avoid such laughter, mimic their elders and make a credible run at the ring.

Again, on the first run, nobody succeeds, but there are still several more runs to come.

Now, as the men gather, more serious than before, we realize that honor is at stake, s well as bragging rights and perhaps a wager or two. The winners here will ride tall through the crowds, feigning unawareness of the eyes following their every move.

Gauchos have no fear of dressing up. Around his waist each gaucho wears a wide belt decorated with embroidered patterns or silver coins. Tucked into each belt is a facon, a long, curved knife, which is a gaucho’s proudest possession other than his horse.

The second round of competition begins. One by one, the riders whirl into attack, their rhythmic whip-slap inciting the crowd. The first to spike the ring is an angular blue-eyed Adonis in a narrow-brimmed hat. Then there’s a younger man wearing a woven vest and carrying his lancet in his teeth. Finally, the crowd parts further to welcome a weather-beaten older man with the inner authority of a foreman—his elegant ride and thrust bring loud applause.

At last, the youth prance out for another turn. Again, the youngest struggle to stay upright, fumbling their lancets. In this twilight of the macho world, there is one young girl with long dark hair almost to her waist. She rides a squat, fat pony and appears to have little hope of keeping up. Yet in her final ride, with the crowd applauding in sync, her pony trots her straight down the middle of the street and she rises up and spears the ring! The crowd goes wild, and the girl beams. When she wheels her pony back around to return the ring, it is waved off and given to her to keep. She won’t forget this day.

Aside from the sortija, the most symbolic part of the Feria is the street dancing. This young girl knew all the steps, and was thrilled to be chosen as a gaucho’s partner.

Originally published in Verge (Canada), Fall 2009