22 March 2013

As the world rushes to embrace GPS and MapQuest and other forms of electronic dependency, it saddens me to see more and more people who are incapable of grasping not just the utilitarian value of maps, but the joy of discovery to be found within them.

Sure, there are plenty of times when one’s sole object is to get from point A to point B in as efficient a manner as possible (though even then I’m always attracted to the additional context provided by a decent road map). But life is about taking side turnings, and dodging roadblocks, and following barely glimpsed tracks off into the unknown. When I sit down to pore over a map history unfolds, geography is laid bare, the lay of the land reveals its secrets.

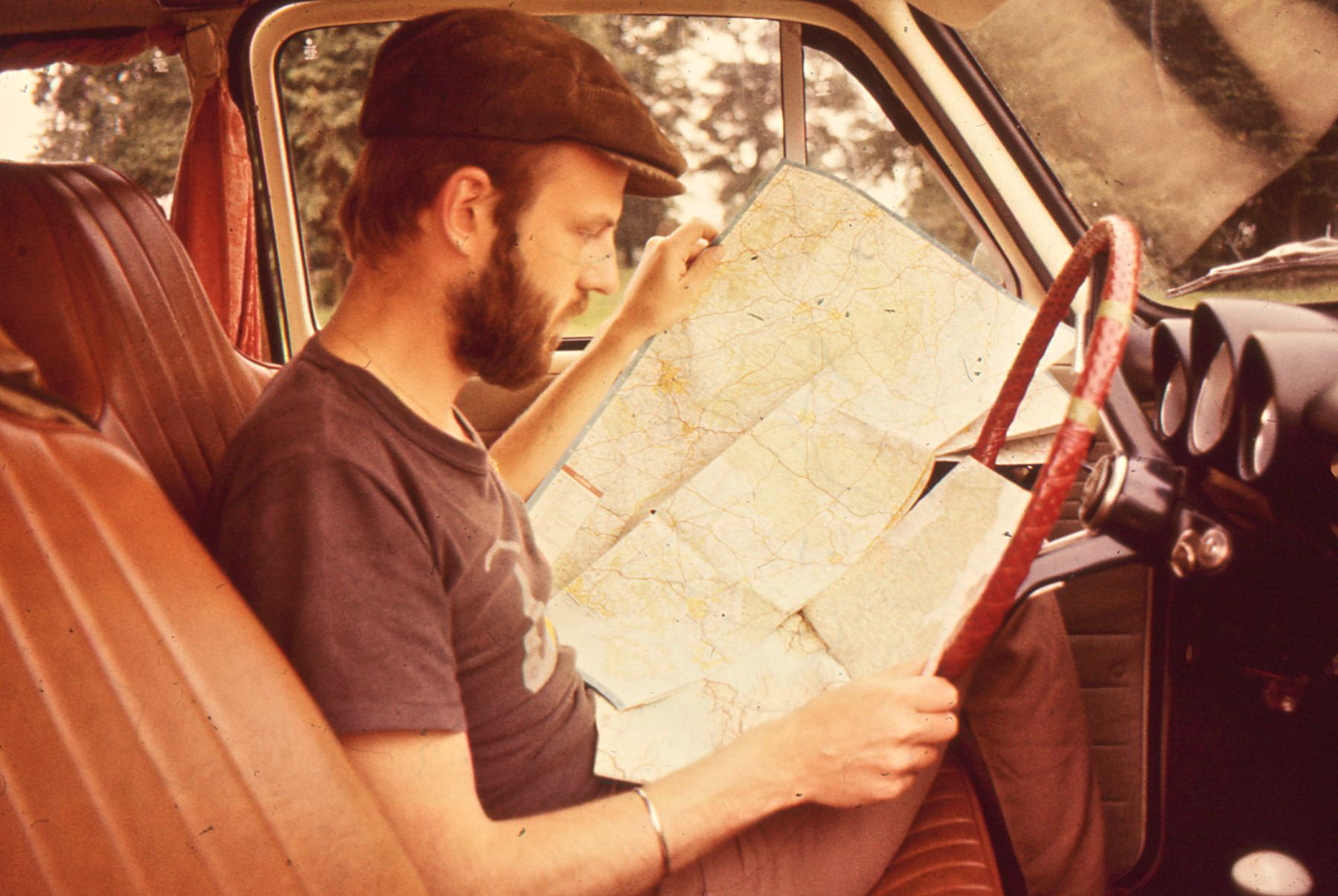

Each morning I’d climb out of my sleeping bag in the back of the car, slide into the front, and start scoping out the day’s possibilities. British Isles, 1978.

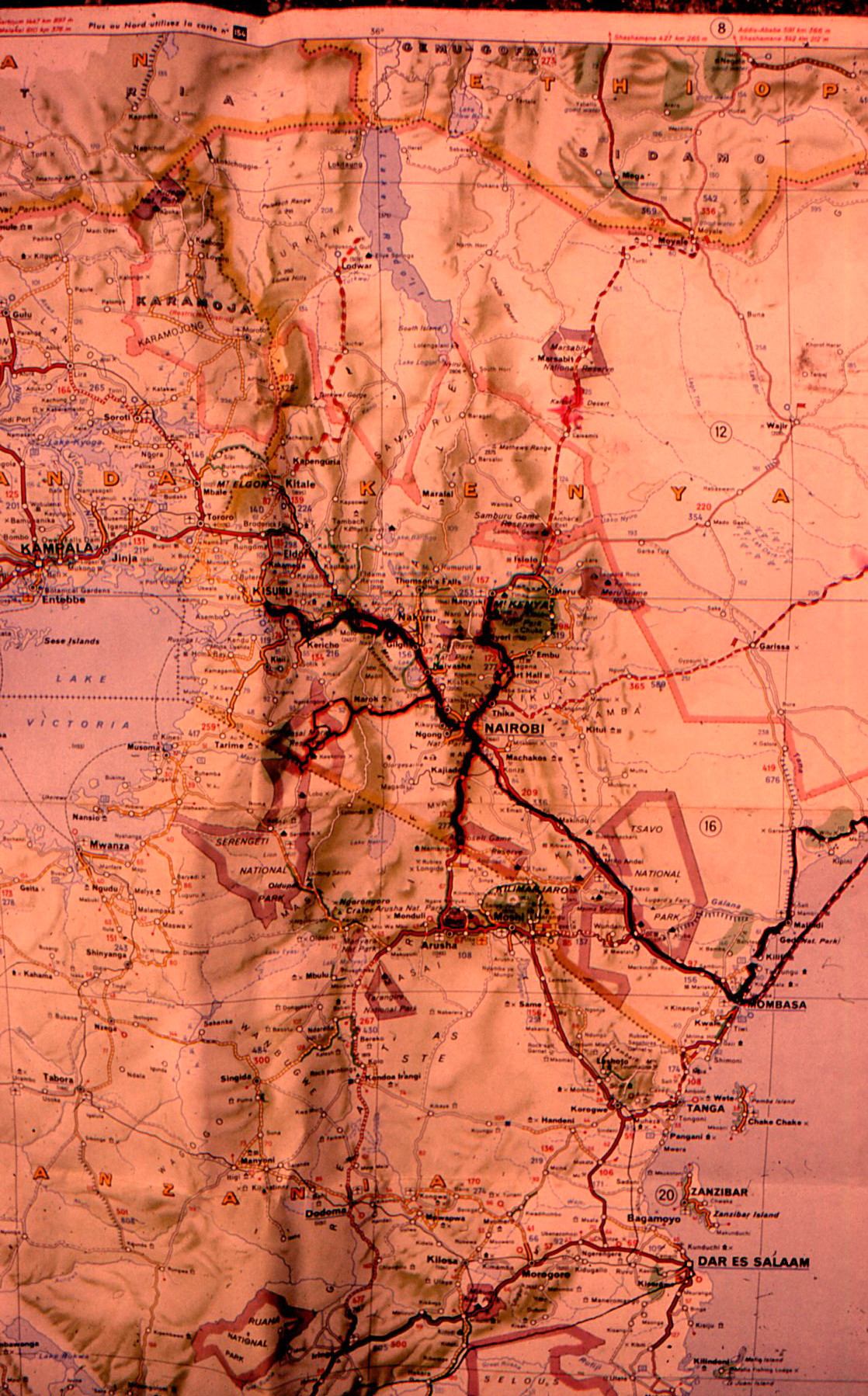

Does that dusty-looking roadway along the winding river eventually lead to a bridge? Where along the edge of that lake might be the best camping spot? What’s the altitude and how steeply do the hills decline on the far side? Is there a pass, or a barrier, or just a smuggler’s track across?

Or: look how that town sprawls across the border—though the border isn’t even open. What’s that symbol for a fortress doing on the hilltop—are there crumbling walls, or just a dungeon left behind? Here’s an historic site; there’s an overlook. How is it that pieces of Belgium and the Netherlands are sprinkled like splattered paint on either side of the frontier?

Or this: just reading through the place names can trigger memories of battles fought, passes crossed, or the tug of war between colonial powers. Why would a site on the Namibian coast be called Luderitz? If a place name says Leningrad what does that tell me about the era in which the map was created? Should I refer to the city as Georgetown or Penang?

When Dexter Doyle studies his maps in Twice a False Messiah he sees abandoned camel routes listed with a dotted line . . . wells marked optimistically as “good water” . . . isolated settlements in the desert persisting without a road anywhere nearby . . . markings for “Ruins” that immediately evoke antiquity. . . . It is the very map itself that allows him to dream his way forward, and many is the time I’ve done that very thing myself.

I can fold my maps down to focus on a single city and conjure walking routes for the day, or open them out to sprawl across a dumpy hostel bed and expand my vision of the possible. I can mark my passage and return to it days or years later, reliving the trail I traversed and conjuring sights and smells so that the journey comes alive once more. I don’t want to be TOLD which way to go. I want to discover that for myself.

I completely agree, Daniel. Maps are mysteries, joys to peruse, dreams waiting to happen. As a traveler, they are my key to a secret passage. As a poet, maps are prompts for poems hovering out there, waiting to be discovered.