20 May 2015

His first year in T-ball I went to every session. The practices were nothing. Nate had that stuff cold. The other kids would be struggling to fit their gloves on and ol’ Nate’d be asking the coach how come they couldn’t steal. The first day, when the coach had asked them to run out to their favorite positions, Nate trotted straight out to second and turned around, pushed his glasses up on his nose, and started to pound his glove. Most of the others were still clustered around home plate, fighting over who was going to get to bat first.

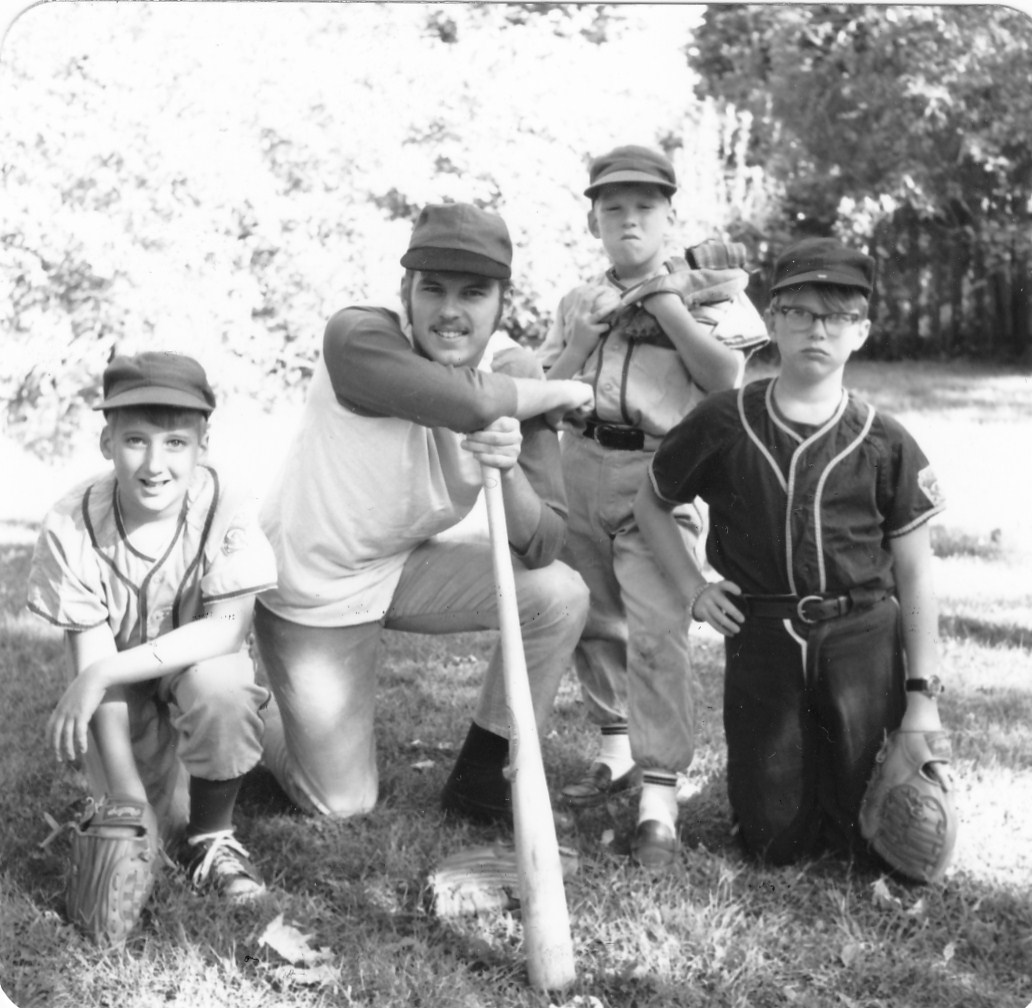

I figured he could be a phenom. Why not? He had me to work with, able to pass on all the accumulated lore of my thirteen years, as well as hand-me-down bats and last year’s baseball cards. He couldn’t use my glove because I was left-handed, but I’d helped him pick out his own and he rubbed it faithfully with neatsfoot oil every Saturday night before his bath. What more could be involved?

Size? No way—this wasn’t basketball or football. Look at Albie Pearson, I told him, or Nellie Fox. Or even “Little John” Johnsrud, who pitched for Neinstadt Drug and could throw a curve ball past any hitter in our league.

He’d never say much. Just focus hard behind those glasses and look somewhere far away, with his forehead bunched and tightened.

T-ball went fine, really. Nate played second every game but one, and if he missed a few he should have had, well, the others missed a whole lot more. He even tried to turn two one time (unassisted at second), but the first baseman was picking his nose and never even saw the ball sail past.

The only real trouble was at the plate. Sitting behind first base, as I usually did, I could see every gap in the field and I expected Nate to hit them. When he didn’t, I got mad. Showed him how it was done, back in our yard. Didn’t use any silly tee either. I told him he’d soon be done with all that nonsense and it was time he learned to hit properly and why in the world couldn’t he see that an acute angle meant pulling the ball and an obtuse one let you hit to the opposite field. I mean, I showed him, for cris’sake. Over and over.

What good is a big brother if he can’t help you lick bad habits before they settle in? I held this notion tight against me, sure of its truth even though I had no big brother of my own. It was my duty to teach—and Nate’s duty to learn. Nobody ever said it would be easy.

By the time he hit Little League it was no use trying to practice hitting in our yard. Half the game was spent chasing balls across the adjacent lots or devising complicated rules to discourage window-level line drives. Besides, I was barely hitting .250 in the Babe Ruth League and beginning to doubt my own wisdom as a hitter. I decided it was time to refocus on fielding.

We gathered in the yard every evening: the two youngest boys, Kev and Monkey, watching from behind the big elm tree like anthropologists observing an arcane tribal ritual. Nate would hustle out to stand against the slat fence of the disused dog pen, push his glasses up on his nose and look at me with a tense, worried expression that showed itself in a tightness along the jaw line. Then he’d pound his glove once or twice and we’d be ready to go.

I’d flip the ball up and lash at it, slicing downwards to send a grounder skipping past the bare spot of our pitcher’s mound and out to second base (a worn, middle slat of the fence), where Nate would bend, scoop, and flip the ball back to me. Or so we hoped. But if I hit a grasscutter, or the ball caught a pebble or a rise in the ground, the hop would come up as uncertain as Monkey when you gave him a choice of three different ice creams.

Nate was quick, but even so many a shot would catch his knee or his hand or sometimes his chin. He’d stand over the ball, glaring down at it like it had bitten him on purpose. Then he’d give a shake wherever it hurt and wing the ball back in to me.

“Head down! Stay with it!” I’d yell, and hit him another. Bang—over the grass to rattle against the fence. “Get in front of it. Stay down.” Another shot. “Keep that head down.” Flip the ball, whip the bat through another arc, ignore Kev wincing behind the elm . . .

It wasn’t meanness that propelled me; at least, not the way I understood meanness. It was love, or maybe a kind of pride. When you’re talking family pride it can get hard to separate the two. Maybe I bore down extra hard because Nate was small. Even Jo-Jo, the bug-eyed redhead from next door, was taller and Smitty, Nate’s lanky best friend who lived across the street, towered over him by a head and a half. So Nate needed to be extra tough, I figured—and would have to work extra hard.

Keeping your head down on a bad hop grounder was not the easy play a big leaguer made it seem. I knew. It was the biggest trouble I’d had playing first base and might well have prompted my third year Little League coach to move me out to center field. I’d been upset at first, railing with youthful myopia at the foolishness of moving a player out of position who’d already put in so many years there, but I’d soon discovered that the outfield had room for my speed and arm that first base had never offered. I still didn’t like bad hop grounders, but by then I’d begun to work on Nate, and I was able to displace the memory of my own deficiencies.

Nate took grounders by the hour, bobbing and pouncing with all the intentness of a cat toying with a rubber mouse. My bat would move faster, rattling the fence on grounders beyond his reach. Bend at the knees, push up the glasses, dive and pounce . . . pound the glove, push up the glasses . . . pound the glove, bend at the knees . . .

He never smiled. The tenseness never left his jaw. Never could see his eyes too clearly either, what with those glasses and the low, tight way he pulled the brim of his hat down over his forehead, darkening his features and leaving a trace of shadow like an ungrown beard across his cheeks.

The only time he looked happy was when it was over and we’d stump on up to the back porch to drop off our gloves and gear. Kev and Monkey would trail us in, wide-eyed and holding each other’s hand.

“Didn’t it hurt, Nate?” Kev would say and Nate would flash that rare grin. “No more’n a kick in the teeth,” he’d say, trying not to rub the bruises on his shins.

“Will I have to do that some day?” Kev would go on, but before anybody could answer, Monkey’d put in—talking real slowly, with his forehead furrowed toward the ground—”But a kick in the teeth hurts a whole bunch.”

This piece was previously published in Elysian Fields Quarterly, Fall 1994.