19 June 2013

Last winter I started getting calls from Nicole London, a WGBH staffer in Boston, asking questions about how it was that I knew the late lamented playwright, August Wilson. (For those who have not yet discovered the man, his Century Cycle of 10 plays about African American life in each decade of the 20th century stands as one of the greatest achievements in the history of the American theater. He won two Pulitzer Prizes, and has a Broadway theater named after him.)

I could tell that they’d spotted my St. Paul Almanac piece, “August Wilson’s Early Days in Saint Paul.” (See link on Home page, under Upcoming Events. August and I were writing partners for years, and given that our wives were close friends at that time, we also shared many other adventures as well.) The more we talked, the more excited PBS seemed to become. Eventually, they decided that they’d better add Saint Paul to their filming schedule. They’re in the process of completing a major documentary on Wilson that will air in the Fall of 2014, and prior to our discussions, had not seemed to fully understand the pivotal role that his time in Saint Paul played in the development of his oeuvre.

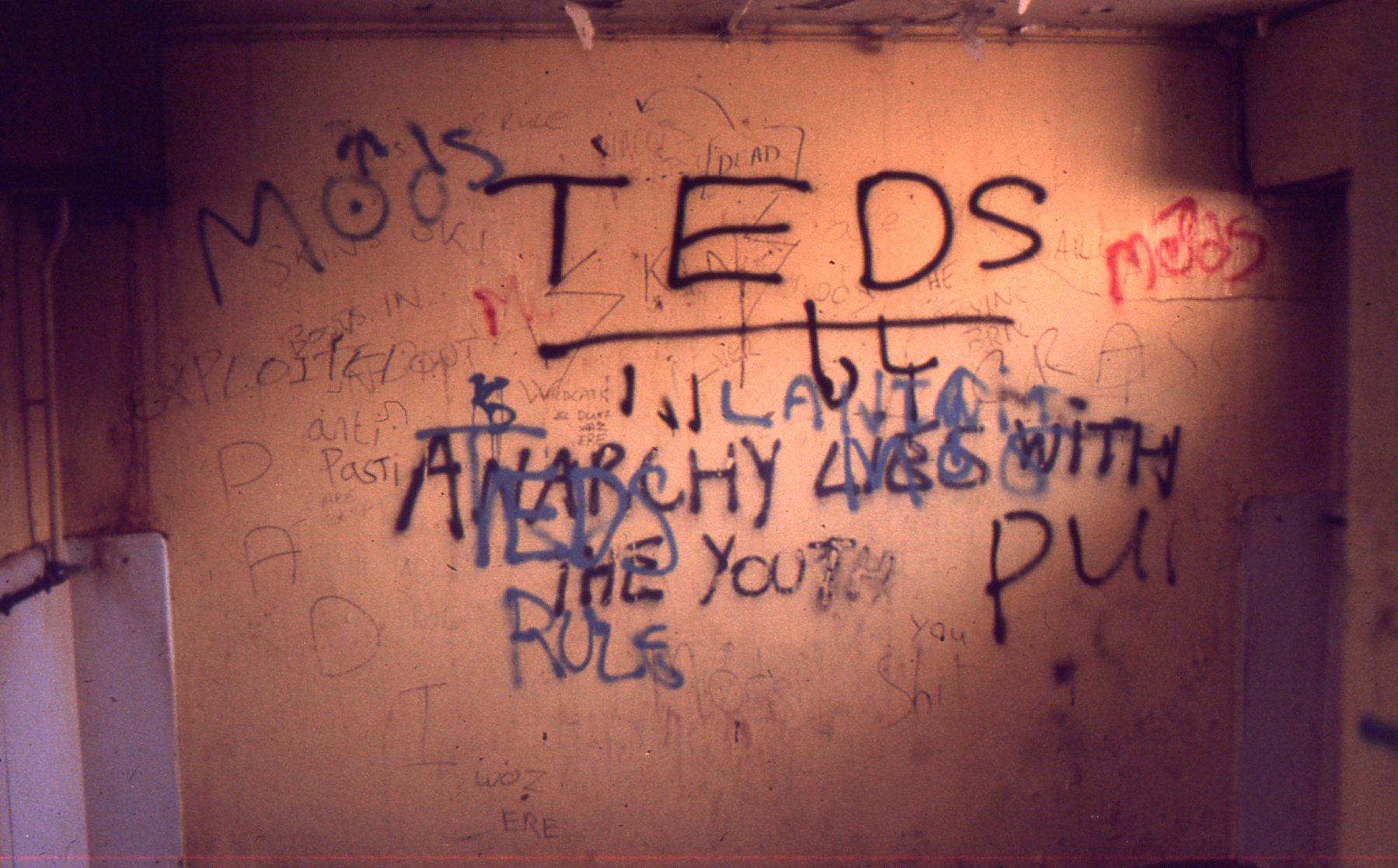

1981: Daniel & Judith Gabriel outside August Wilson’s Grand Avenue apartment in Saint Paul, with the man himself and—I swear—a casual passerby whom August’s wife Judy insisted be in the photo.

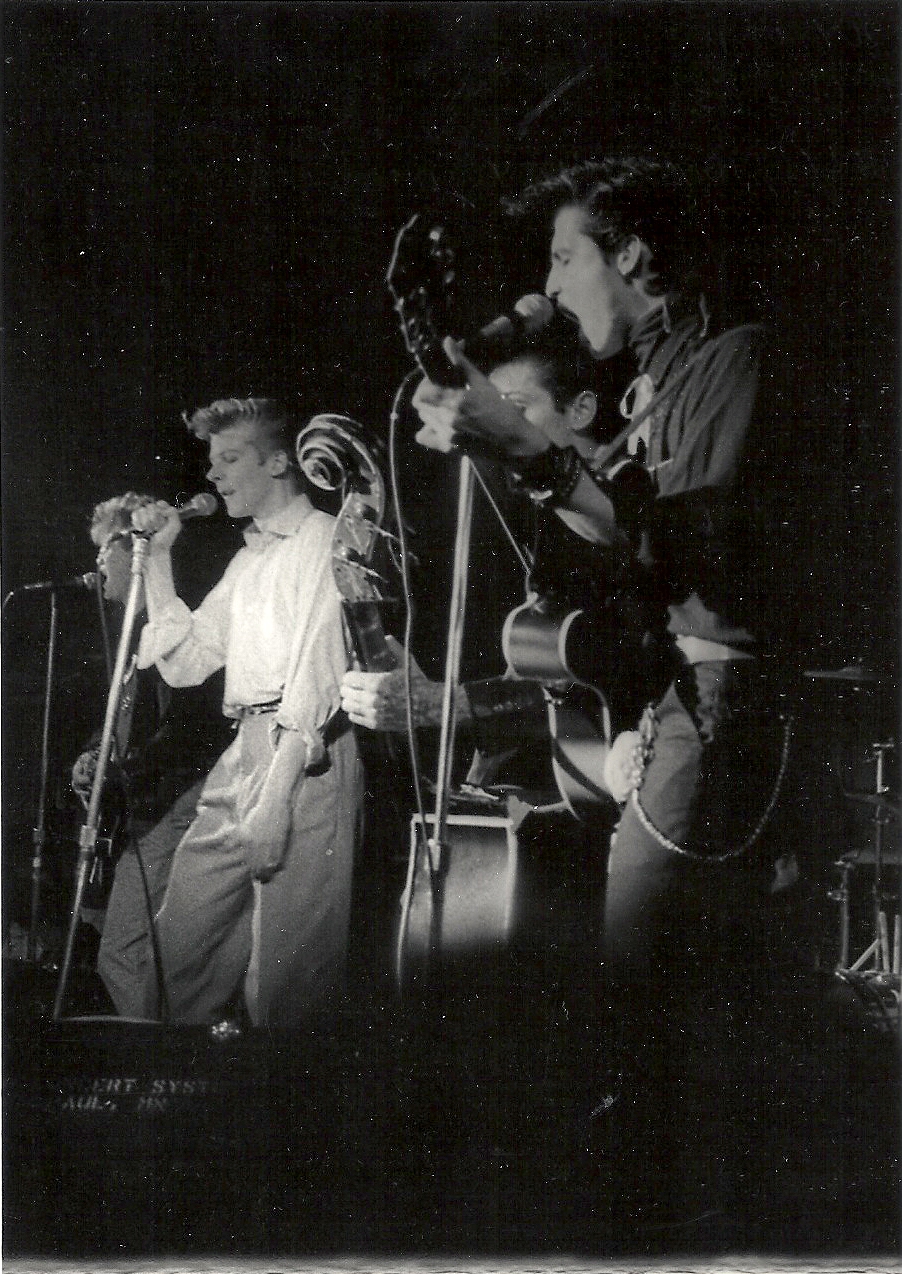

Late in May, producer Sam P, Nicole L, and crew rolled into town and set up in Penumbra Theater, home to more August Wilson productions than any other theater in the world. They ran me through my paces during a 20-30 minute interview, and then ravaged the piles of memorabilia I’d brought along. There were posters from the Penumbra productions of Wilson’s first plays, early draft manuscripts of his first major successes, and obscure reviews that had appeared down through the years. I also had photos from the night he won his first Pulitzer Prize (for Fences). A handful of us gathered to celebrate and hear him declaim a fatherhood scene from the play, and he held my infant son Alex in his arms as a prop. There were also over a dozen rare letters from him to me, including sections (which I’d long forgotten) where he lamented that he was giving up on Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (his first breakthrough play), and others where he offered tight-knit advice on pieces of my work that I’d sent him.

1987: On the night that FENCES won the Pulitzer Prize, young Alex Gabriel gets his first exposure to the power of a scene declaimed by August Wilson.

Hanging out backstage with the folks from WGBH, and jiving about the various bits of memorabilia and their significance was even more fun than the actual taping. (By the next day, of course, I’d thought of all sorts of comments that I wished I’d made during the interview.) What really seemed to hit home to the producer was that Wilson’s time in Saint Paul marked that magical period in any great creative artist’s life when they find their true and authentic voice, and discover how to control it. I can still vividly remember the sessions of sitting across from August in some funky cafe, listening to him riff and ramble until he found his way into a scene–and then watching him catch his rhythm and start muttering aloud the rough drafts of what later became full-blown scenes in his iconic plays. I had the great privilege of watching a clutch of August Wilson Broadway hits–Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Fences, Jitney, The Piano Lesson, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, etc.–find their earliest shape.

The single most vital piece of transformation in Wilson’s approach came as he shifted his characters’ dialogue away from Borges-esque convolution and wordplay into the deep declarative poetry of the Blues. Once he’d learned how to turn his plays into overlapping Blues songs (with each character playing their own notes, or at times producing their own countervailing songs) the rest was a matter of harnessing his active and fertile imagination.

August Wilson died in 2005, his Century Cycle complete. But I still listen hard for his advice every time I sit down to write. And I can still see those piercing eyes pushing me forward along my own writing path. Like the man said, “If you’re going to Brownsville, got to take that right hand road . . .”